The Imaginary Institution of India, Barbican, exhibition review: ‘Sure to open eyes and touch hearts’

An installation view of the display. Photograph: Eva Herzog Studio / Barbican

In partnership with New Delhi’s Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, the Barbican has brought together 150 works by 30 Indian artists in a stunning new exhibition of painting, sculpture, photography, installation and film.

The Imaginary Institution of India explores social change during the seminal period of history that stretched from Indira Ghandi’s declaration of a State of Emergency in 1975 to the country’s decision in 1998 to end its long-established policy of military non-aggression and undertake nuclear tests.

The show takes its title from an essay by Sudipta Kaviraj, which reflects on the complex process of seeking to embed democratic orientations in India’s diverse society.

Bhupen Khakhar’s Grey Blanket, 1998. Image: Estate of Bhupen Khakhar

The late 20th century was a period of rapid development, when the aspiration of India’s leaders to remake their country around modern secular values often shot ahead of the social reality on the ground.

Rich seams of cultural heritage give meaning to lives on the subcontinent, yet traditional norms are at times in tension with the ideals of equality between social groups, genders and sexualities.

The exhibition is organised around four themes: urbanisation and shifting class structures; the rise of communal violence; gender and sexuality; and a growing connection with Indigenism.

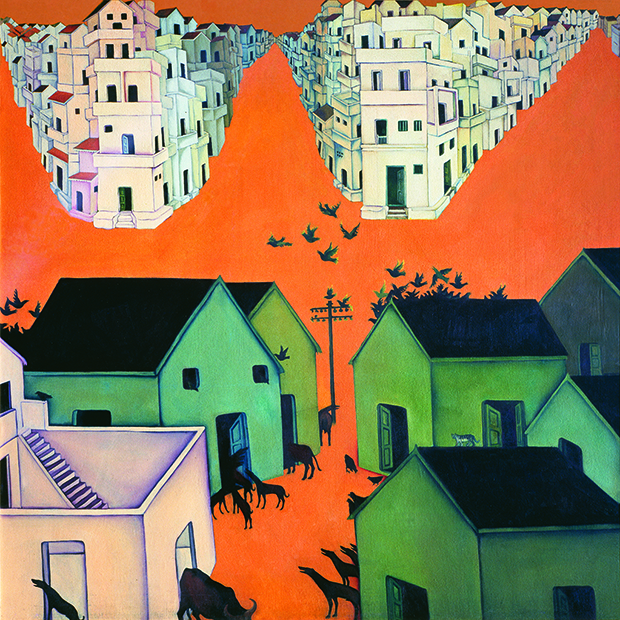

Gulammohammed Sheikh’s Speechless City, 1975. Image: Gulammohammed Sheikh / courtesy the artist and Vadehra Art Gallery

The response of artists to social and political developments varies from protest – as in Navjot Altaf’s bold screen prints depicting industrial action and demonstrations, Sheba Chhachhi’s striking portraits of women activists, and Sunil Gupta’s radical photos of gay men in the 1980s – to nuanced reflections on cultural change, as seen in the urban panoramas of Gieve Patel and the dreamy flowing colours of Nilima Sheikh’s intimate personal scenes.

Disquiet at India’s sudden political and economic lurches haunt many of the works collected here, including Rummana Hussein’s installations on communal violence, featuring shattered pots, spilt red clay powder and other oblique reminders of lives destroyed.

On a lighter note, C. K. Rajan’s witty collages of magazine clippings offer wry commentary on the effects of rising capitalism. And perhaps most powerful is Remembering Toba Tek Singh, Nalini Malani’s large-scale video triptych on the theme of nuclear weapons development.

The sheer variety of the art on display is perhaps the most impressive thing about this show, which is sure to open eyes and touch hearts.

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998 runs until 5 January at the Barbican.