‘We used to understand the beauty of something being made by hand’: Jeweller Theo Fennell on the East End, his burgeoning writing career, and how big brands are sucking the joy out of his craft

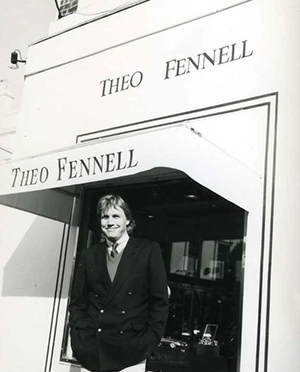

‘King of bling’ Theo Fennell started his career in Hackney. Photograph: Theo Fennell Jewellery

Theo Fennell, the famed jeweller known as ‘the king of bling’, is loved by celebrities for his glamorous designs.

Now the 70-year-old, whose glittering career began in Hackney, has revealed he is working on a sequel to his hilarious debut memoir, I Fear For This Boy: Chapters of Accidents, which was published last year.

The first book takes in his time as an apprentice and charts his rise to becoming a jeweller for the stars, with fascinating stories and insights into the East End and Hatton Garden in the 1970s.

Fennell told the Citizen: “I think the second one will be more of the same, but further on in my life. Again a fun one.”

While waiting for that to drop, I Fear For This Boy is well worth a read.

The book started as a humble lockdown project, with Fennell aiming to produce 50 copies for friends and family.

It was later swept up by Hackney publisher Mensch, and described as “one of the funniest books I have ever read” by novelist William Boyd.

Fennell explained: “A friend said ‘Do you mind if I send it to a publisher?’ and then the whole thing started getting serious. Suddenly I had to start thinking about literary festivals.”

He wrote the book for his daughters, filmmaker and actress Emerald and fashion designer Coco, who had concerns.

“They stipulated that there should be no famous people [in it] because otherwise it becomes a totally different thing,” Fennell said. “And no sex because they would all be deeply embarrassed and it’s too disgusting the idea of father even kissing anyone.

“And I shouldn’t be mean about anyone – why would I? There’s no point.”

He joked: “So all of that took away about three quarters of the stories.”

The book’s honourable intentions do not stop it being filled with fun, scandalous stories.

A younger Fennell outside his shop. Photograph: Theo Fennell Jewellery

Fennell is a master of wry self-deprecation, particularly about being a Chelsea boy in Hackney.

The book starts with a Cockney policeman laughing at the irony of Fennell’s security dog being stolen by burglars.

He goes on to describe a time in Hackney when the jewellery industry was a hotbed of crime and dodgy morals.

When Fennell complains to police that someone had tried to sell him some of the wares stolen in the heist, a complicit officer tells him to do one.

“I met a very serious journalist who read the book and was very worried I had such a destructive life and things went to so wrong all the time. I said it really wasn’t like that, it was great fun.”

Fennell talks passionately about his time learning in amongst the grit and groundedness of the area.

He fondly remembers people he met in East End pubs who had lived through the First World War and seen Hackney in terribly tough times – right back to Victorian days with one street sharing a toilet.

“People I met had seen huge changes in their lives. They were fascinating. And they were very, very funny.”

He added: “There were lots of war stories of Ronnie and Reggie, the Kray twins, and the night this happened or that happened, which were about as likely as most war stories are.

“There was such a cross-section of backgrounds and cultures. It was just terrific. So it was a really interesting place to be. It was a very action-packed time.”

Fennell apprenticed with a silversmith in Hatton Gardens.

He said: “I realised in that kind of family business that there was only so far you could get and only so far it would change. But in those days everything was moving so fast and everything was changing. I thought I can’t do this.”

He said his next step, renting a studio and flogging his designs at Portobello Road and Kensington Market, felt casual at the time.

“It was a pretty inept, inefficient, go-as-you-do kind of thing. If we had enough on Friday to last us the weekend we were happy. There was no intentions of forming a business or a big old thing. We’d make a few quid, and then we’d spend it and then we’d start again.”

He started to make a name for himself when he was travelling around London selling bespoke work, followed by opening up a shop on Fulham Road.

“There was no social media and we couldn’t afford to advertise, so the only way we could get ourselves known was to go to as many parties as we could and hand our cards out.”

Despite huge technological shifts, such as social media and computer-aided design (CAD), Fennell maintains that ancient jewellery techniques have remained timelessly relevant.

“If I brought my 25-year-old self into this year, I wouldn’t really notice much change,” he said. “Obviously I’d notice computer imaging, but we don’t use much of that compared to hand-making things properly.”

The strong onus on handcrafting in jewellery meant it was one of the last industries to fully embrace CAD.

Another major shift in jewellery since the 1970s has been big brands, usually makers of other goods like clothes or luggage, entering the market with the ability to mass-produce.

Fennell said: “The billions businesses spent on advertising brainwashed the public into believing that something they sold 25,000 of a year was all handmade by brilliant craftspeople.

“These businesses were charging vast amounts of money and sticking their name on the side so suddenly it becomes an advertisement for their brand.

“A 30-carat diamond on a ring is a statement. It’s beautiful, but it’s just a lot of money stuck into one thing. All it is is a statement of wealth and very often ownership.

“But when you see jewellery in the Louvre, you look at it in a visceral way. You look at it with the heart rather than the mind. You think about the emotion, passion and the sentiment gone into it.

“You start to appreciate craftsmanship and skill, even if it’s rudimentary because it was made in the 15th century. You still know that the skill level needed to have done it at that time was extraordinary.

“Before the big brands, we understood the beauty of something being made by hand. But all of a sudden fortunes were being made so quickly that people didn’t have time to learn about great pictures or great furniture, for example.

“Now we get beaten over the head with the same things. It stops people having joy.”

Fennell’s own jewellery and silverware certainly evokes keen craftsmanship with its ambitious detail. One example is a signet ring that opens to reveal a dainty Stonehenge construction. Another is a pair of cufflinks adorned with intricate paintings.

He is in the process of recounting his jewellery collection through the years in yet another writing endeavour.

“When I was young I had all these writerly ambitions that I think many people have, until you realise how difficult it is to write a novel and how 100,000 people are also writing a novel.

“You get to the age of 70, when I wrote my book, and you don’t think you’ll be starting on a new phase of your existence.”