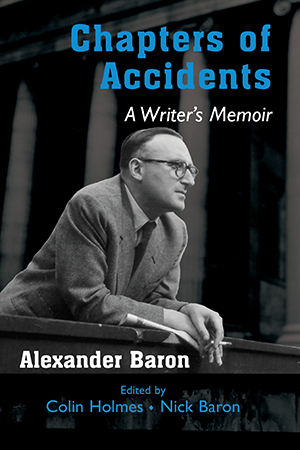

Chapter of Accidents: A Writer’s Memoir, Alexander Baron, book review: ‘Portrait of a man keen to be accepted but feeling himself apart’

Alexander Baron was an atheist Jew, a former Communist and an ex-soldier. Photograph: Clayton Evans / courtesy Nick Baron

The period between the 1930s and the 1950s was one of feverishly concentrated politics, tragic violence and social upheaval that ultimately ushered forth a social and political order that has remained with us to this day.

East London was at the epicentre of key events such as the Battle of Cable Street, the Blitz, and Commonwealth immigration, and the novels of Alexander Baron make sense of this turbulent era from the ground up.

Born into an East End Jewish family who later moved to Stoke Newington, Baron excelled at his local grammar before being seduced as a schoolboy into a six-year romance with the communist movement, for which he worked ferociously hard as a magazine editor and writer.

Just as he was becoming disenchanted with the cause, he was called up to fight in the Second World War, serving with General Montgomery’s Eight Army in Sicily and then being among the first troops to land on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day in 1944.

When he was eventually demobbed in 1946, all he asked for was a typewriter, for he had by then found his calling.

During a career as a novelist and screenwriter that spanned four decades, he wrote 15 volumes of fiction, many of them drawing on themes that can be traced to his childhood and the frenetic years between 1934 and 1945 that did so much to shape his outlook.

Chapters of Accidents: A Writer’s Memoir is Baron’s chronicle of his life up to the publication of his first novel in 1948.

Written some 45 years later, it has now been published under the editorship of British historian Colin Holmes and the writer’s own son Nick Baron, who is a historian of Russia and the Soviet Union at the University of Nottingham.

Baron (top left) rose to prominence through his war novels. Photograph: Nick Baron

Alexander Baron was initially best known for his war novels, in particular From the City, from the Plough (1948), which offered a gripping soldier’s view of life on the front lines and has sold over a million copies.

More recently, his East London novels have come to greater attention, especially Rosie Hogarth (1951), The Lowlife (1963) and King Dido (1969), which portray the social intricacy and distinctiveness of the area at different points during the 20th century.

When postmodernism hit and fashions swerved in the 1970s and 1980s, critics were less in tune with Baron’s realist style, although his books continued to attract a dedicated readership.

In recent years, as we again face social upheaval, there has been a major surge of interest in his work, with a new generation attracted to their rich layering, variegated characters and vivid portrayals of particular localities.

The portrait sketched in Baron’s memoir is of a man who is diffident but intense, shy but at ease with his natural leadership skills, keen to be accepted but feeling himself apart.

Already as a child other kids would gather in the street to listen to the stories he told, and fellow soldiers rallied round him in the army.

At the same time, he seems often to have felt that he was watching social interaction from the outside.

“I have never known how to draw people out to talk”, he says, and he felt he “lacked some kind of psychic antennae which other people possessed”.

He was for all that a keen observer of people, a voracious reader, and from a young age writing became a “need”.

Portrait of Alexander Baron in London, early 1960s, on the memoir’s cover. Photograph: Clayton Evans / courtesy Nick Baron

At a book launch held at Hackney Archives at the end of September, Nick Baron explained how his father had seen his memoirs as holding the key to his writing.

Yet far from narrating an inevitable path from childhood through formative years to creative production, the novelist depicts a life shaped by contingency.

His ‘theory of accidents’, which gives the book its title, may be a reaction against the Marxist historical determinism he ultimately rejected, but on a more personal level it is also a tale of opportunities missed, paths not taken, people not acknowledged along the way.

There is a sense of wistful regret that dedication to the Communist cause led Baron to give up the chance to attend university and pursue a contemplative life.

At the same time, fortune also threw the nascent writer into encounters with André Malraux and Louis Aragon in Paris in 1935 and J. B. Priestley in London a decade later. It afforded him an influential role in shaping the minds of left-wing youth in the 1930s, and it led to associations with other writers and intellectuals, including Ted Willis, who helped Baron find his feet in the early post-war period when he was starting out as a novelist.

I asked Nick Baron whether there was a particular event that had prompted his father to write his memoirs, and he said: “I think dad started writing these in 1993. I assume that he always intended to write something reflecting on his youthful engagement with communism.

“I know that dad conducted quite a bit of research for the memoir, trying to find out more about events and personalities either that he only half-recollected or that he had not fully understood at the time. So I imagine that the immediate catalyst for writing the memoir was the opening of the Soviet archives after 1991.

“I think it was the collapse of the USSR as a geopolitical event that, perhaps, seemed to vindicate my dad’s rejection of communism forty or so years earlier.”

The imprint of the novelist’s engagement with communism clearly still loomed large even half a century on.

I also wondered whether his father had ever felt he belonged to a literary fraternity in the same way that he belonged to the Communist cause or to the Army.

Nick Baron replied: “My father certainly felt a sense of belonging in the CP [Communist Party] and then in the Army, as you say. I wonder, though, if wrenching himself out of the CP, and then injury and mental trauma in the war, didn’t prompt him later to treat any collective with some suspicion. He never, as far as I know, associated closely with any ‘fraternity’ or clique.

“This is not to say he wasn’t a very convivial person, who had some extremely close friends with whom he met regularly and with whom he stayed close for decades, including many writers – Mervyn Jones, Manny Litvinoff, Alison McLeod spring to mind – as well as other ‘creative’ types such as Oscar Lewenstein. But I don’t think he was in any way drawn to the ‘literati’ of his time.”

Being at one remove from fashions and movements is perhaps precisely what enabled Baron to provide such compelling portrayals of the human condition that are as fresh and relevant today as they were decades ago.

Chapters of Accidents: A Writer’s Memoir by Alexander Baron, edited by Colin Holmes and Nick Baron, is published by Vallentine Mitchell Books. ISBN: 978 1 80371 029 7; RRP: £16.95.

Until 14 March 2023, the publisher is offering a 20 per cent discount (not including post and packing) for those who buy the book at vmbooks.com; use the code ‘Baron22’.