The Citizen Gardener: ‘Humans shouldn’t always be at the centre of decision-making’

Not long ago I became a blue tit for a day. I was on a group walk as part of ‘More than Human: Data Interactions in a Smart City’, a collaborative research project, organised by City University of London, exploring how non-humans experience the city.

We all took on the ‘persona’ of a different animal or insect and attempted to view, hear, feel, smell and even taste the environment in a different way. We thought about how and where we might rest, reproduce, eat, shelter, compete, hide, get rid of waste, die and do all the other things animals do.

The point was to have a different perspective on the information local authorities, planners, architects, designers and ecologists collect to make decisions about how our neighbourhoods are designed. Perhaps, and here’s a thought, humans shouldn’t always be at the centre of decision-making?

Being able to see the streets from a different point of view makes you realise what a struggle nature has to survive. Those that benefit from living alongside humans like foxes, rooks, rats, squirrels or magpies do fine as they make use of our waste.

In the early months of the pandemic they faltered as we weren’t leaving boxes of chicken bones on the pavements, stuffing rubbish bins to overflow in parks or wasting food on our plates in restaurants. Still, we’re getting back to normal so that they can perform this useful cleaning-up role for us. The smaller creatures like insects, though, rely less on our wasteful habits and more on plants to provide their food and shelter.

Usually our streets are designed with cars and humans in mind. Greenery is less of a priority, which makes it harder for wildlife for thrive.

If they do survive, insects do the pollinating of our food and flowers, an amazing job of recycling waste and nutrients, provide natural pest control and also become food themselves for other animals. Knock a plant, and so a specialised insect, out of the system and a whole chain of animals could go with it – including the furry or spiky ones that we so love.

‘Urban planning needs to be integrated into nature’

The mayor of Curridabat, a suburb of San Jose in Costa Rica, not long ago gave equal citizenship to insects, trees and native plants with humans. He and his department believe that nature needs to be integrated into urban planning or, rather that urban planning needs to be integrated into nature.

Their planners put nature, in particular pollinators, at the centre of design. The municipality has become known as Sweet City.

As they say in describing their plan (bit.ly/3uISnlJ): “The Sweet City vision recognises pollinators, which are the largest producers of plants, trees, and ultimately soil, as the centre of urban design. By reframing the role of pollinators, and recognising them as native inhabitants and city dwellers, Sweet City overcomes the long-lived antagonism between city and nature that has characterised traditional urban development.”

In our own way we are doing our bit. Monmouth has been named Britain’s first bee town and actively reduces the use of pesticides whilst increasing the number of wild plants in the streets. There is Bug Life’s Bee Lines which aims to join up ‘biocorridors’ across the country, Plant Life’s verges and no mow campaigns which are increasing biodiversity, and here in Hackney there are lots of projects to create pollinator corridors. These corridors allow ‘weeds’ to flourish, reduce the use of herbicides and increase habitat and biodiversity. It seems that the public is becoming more aware of the importance of insects and want to help.

Local writer Vicki Hird’s book Rebugging the Planet describes the situation we’re in (40 per cent of insect species at risk of extinction), the wonder and importance of bugs, and what we can do about this impending crash, not only personally, but structurally by challenging who makes decisions on land and who oversees its management.

All our individual efforts, though valuable, come to nothing if the big players aren’t involved. This is where the greater battle is, because shifting the emphasis towards the benefit of nature (rather than capital or just human convenience) is where the real slog is.

According to Vicki Hird’s figures, agricultural commodity traders (not farmers) are the most powerful companies in the industrial food chain with six companies controlling most of the global food trade. In 2017, four companies controlled 70 per cent of agrochemical sales and 10 companies controlled over 50 per cent of fertilizers. These big organisations have huge resources to lobby and influence politicians and determine how land is used.

We aren’t growing much food in Hackney but we are influenced, for example, by how pesticides are marketed to us or how herbicides are used in our streets, as well as how much greenery is incorporated in or removed by developments.

‘It’s the planners, architects and developers who need to change too’

In Costa Rica the political will was there to persuade the planners to alter their way of looking at the land by putting nature first – for the good of everyone. Change happened.

Hackney does seem to have the political will to make changes; there are individuals amongst councillors and within departments who really do want to make big shifts to benefit nature. But it’s the planners, architects and developers who need to change too. I wonder if they would be prepared to be blue tits for a day.

Growing wildflowers in London

We are often urged to grow wildflowers and meadows to help wildlife but in London we very often have the wrong conditions so our attempts at ‘wilding’ flop.

The most valuable species are often ones that, perhaps surprisingly, live on poor soil and if we want meadow plants to thrive, we need to remove nutrients from the soil to encourage the less showy but more valuable wild flowers. I have found a few plants that are attractive and work well in urban areas and which, just through observation rather than scientific study, I’ve noticed attract a lot of insects.

Corn marigold – they used to grow amongst crops but have been pretty much eradicated now. It’s like a big yellow daisy and flowers all summer.

Sweet cicely – an aniseed-flavoured herb with feathery leaves and clumps of small flowers. It gets quite big, though so cut it back.

Hyssop – another less common herb. It looks similar to lavender and is bushy but flowers later in the year. Give it space. Bees love it.

Garlic chives – The leaves taste of garlic and you can keep cutting them all year. If you let it flower though, they are covered with insects at this time of year.

Scabious black knight – I had some of this growing in a wheelbarrow last year and it flowered for months.

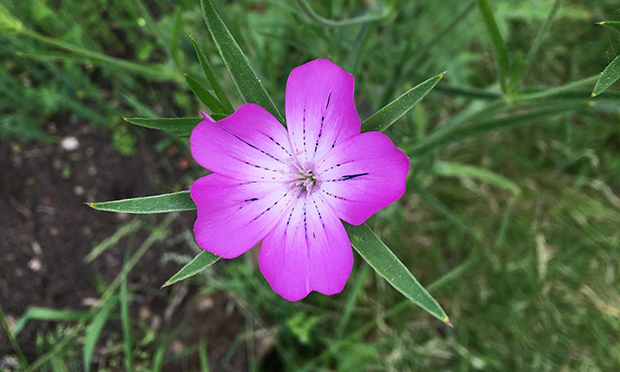

Corncockle – another agricultural flower almost extinct in the wild. It is quite showy for a wild plant with pink trumpets. The seeds are easy to save after flowering.

Buckwheat – used as a green manure but has pretty heart-shaped leaves and frothy white flowers which are popular with insects.

Feverfew – flowers most of the year, will spread into cracks and is meant to be good for headaches.

Kate Poland is an award-winning community gardener. She was chosen to be the UK’s first ever postcode gardener in E5 as part of Friends of the Earth’s 10xGreener project. For more information, head to cordwainersgrow.org.uk and friendsoftheearth.uk.