Yellow on a plate

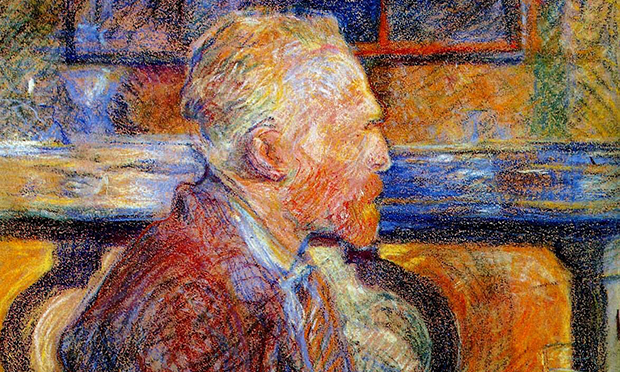

Que c’est beau le jaune! Yellow was Van Gogh’s favourite colour – “the colour of happiness”.

Perhaps the yellow that Vincent loved so much might have found its way onto his plate as well as his palate during the sun-drenched weeks in Arles in the south of France from September 1888 to 1889?

He painted his house yellow, and delighted in the golden cornfields and hot skies of late summer, wanting us to enjoy not just his painting but be taken by the hand for a walk through the glowing landscape, promising decades of happiness and companionship for himself and his friends and fellow artists.

Forget the overdramatised versions of mental disturbance and self-harm, happiness was what Vincent sought and so nearly achieved. His breakdown and the collapse of the idealistic brotherhood of artists living harmoniously in the mellow light of the south contributed to his death in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, not far from Paris, where in the last two months of his life he produced over 70 paintings and drawings.

Van Gogh seems to have had a mind above food, just a bit of bread was enough to keep him going, he often said. So it is interesting that he rejected his friend Gauguin’s suggestion that some frugal home catering might not come amiss. The sad-looking onions with bright green sprouts in several of the paintings indicate a deliberate neglect of kitchen matters.

Vincent instead had most of his meals in the bistro next door. Convenience or pleasure? Couldn’t be bothered to cook? Or was the food too good to miss? Perhaps after a morning’s intense solitary work the painter was glad of the company of people enjoying food and drink, with all the bustle and chatter and kitchen smells mingling with the fumes of tobacco and whiffs of the notorious absinthe, an innocent-tasting drink flavoured with many plants including fennel and aniseed and wormwood (artemisia absinthium), a pleasant herb of the mugwort or daisy family).

This greenish yellow liqueur, the fée verte, as its addicts affectionately called it, becomes a pale cloudy liquid when you add water, and was until recently the victim of a gastro- or rather alco-myth: that the neurotoxic substance thujone, found in oils extracted from wormwood, caused the mental and psychic disorders that afflicted the artists and intelligentsia of the Belle Epoque. They would probably have gone bonkers anyway from their abuse of other substances.

Tests have shown that the amount of thujone in contemporary recipes for absinthe, before it was banned in France in 1914, could not on its own have caused the hallucinations and over-excitement and nervous collapse that overcame so many absinthe drinkers.

The crude alcohol in which the herbs were distilled or macerated, and dubious colouring materials including copper, used to get the pretty greenish yellow colour, were probably the villains.

It was the cheapness of this pleasant, trendy drink that appealed. You could get sloshed for less than the price of cheap plonk, as Degas shows above in his work L’Absinthe, while the well-off created fancy glasses and spoons and little rituals to enhance the guilty frisson of indulging in a dangerous pleasure.

It is not insignificant that both the demonisation and rehabilitation of absinthe were motivated by commercial interests; wine growers, alarmed at the success of a cheap rival, were happy to spread the thujone myth, and support the ban in 1914, while the cocktail industry in the early years of this century were equally happy to demolish the myth while recreating the frisson by promoting a harmless version of absinthe complete with lurid labels.

The year before Van Gogh arrived in Arles, Jean-Baptiste Reboul had published La Cuisinière Provençale, which became a best-seller. Subsequent editions had a bright yellow cover, and many of the local recipes had bright yellow hues. Especially aïoli, a pungent garlic mayonnaise – which has a golden glow when we make it with one of those nice brown eggs from Whole Foods – that was often stirred into bourride, a fish stew, giving it a warm yellow tinge and a huge waft of garlic.

Then there was bouillabaisse, a fish soup made with the many small flavoursome little fish hanging around at the end of the day’s catch along the Mediterranean, a speciality of Marseille, bright and fragrant with saffron and served with rouille. This sauce, made from red paprika and tomato pounded together with bread and much olive oil, gives the cheerful orange Vincent often used alongside various shades of yellow in his paintings. He might have enjoyed socca, a pale yellow pancake made from chickpea flour, cooked on big metal convex pans over intense heat like the farinata of nearby Liguria, or what Reboul calls a pilau, rice cooked without stirring in a rich saffron-coloured sauce of aromatic vegetables and shellfish.

Hackney is unlikely to remind us of Marseille, but it offers a lovely range of yellow food, coloured with turmeric at a fraction of the cost of saffron, and a happy reminder of our multicultural food and drink.