More Lemons

If exotic expensive lemons were out of reach in the past, there were various alternatives: melissa or lemon balm is a gentle kindly herb which was used to comfort the heart and dispel melancholy, helping to overcome depression, insomnia, digestive problems, as well as adding a lovely flavour to salads, sauces, various kinds of booze, and cosmetics.

This versatile plant grows easily in most climates; it was known as a medicinal herb to the Ancient Greeks and Romans, who gave it one of the names we have for it, melissa, a word for bees and their honey; bunches of the herb were put inside and around bee-hives to encourage settlers. We can do this too, by growing our own in a plant pot or window box here in Hackney, good for our threatened bees, and good for us too. It’s one of the first plants to emerge in spring so provides leaves when nothing much else is around. It grows pretty much anywhere; in fact stopping it from taking over is sometimes a problem. Happy in sun or part shade – in the ground or a pot. Chop back after flowering and keep it watered. It’s a member of the mint family and its flowers are attractive to pollinators

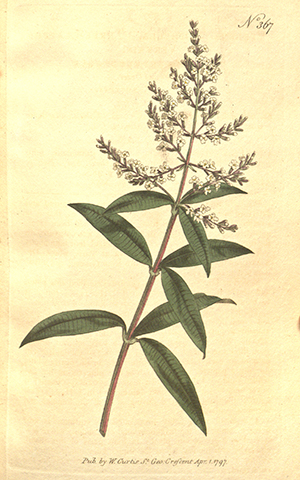

The fresh leaves of melissa give a lemony fragrance but no acidity to salads and stews; they also make a pleasant herbal tea, not as harsh as strong builder’s tea, and with the happy effects mentioned above. Unknown to the Ancient World is another plant that arrived in Europe in the 17th century from South America, and has similar effects and virtues – lemon verbena or hierba luisa, said to be called after Maria Luisa, wife of the Prince of Asturias, an enthusiastic collector of plants for the Botanical Gardens in Madrid. This pretty and very convenient name is only one of many for this much-loved plant, aloysia citrodora or citrón, which has getting on for 29 different names in its native homelands in South America, where it is used to flavour food, cosmetics, herbal remedies and liqueurs. This too can be grown in Hackney, and the leaves enjoyed fresh or dried.

Lemon thyme and basil are some of the many lemon-scented herbs that we can grow here Thyme is a perennial, Mediterranean plant and likes a sunny, well-drained spot. Pick regularly to keep it healthy and prune after it’s flowered to keep it vigorous. Weed around thyme as it doesn’t like competition. Basil is a tender annual plant and needs a sunny position. Start off indoors as its seeds need around 20 degrees to germinate. Humidity helps germination so put a plastic bag over the pot (but remove it later so it doesn’t rot). Transplant into separate pots. Doesn’t like temperatures below 16 degrees.

Our pursuit of fresh herbs for cooking ignores their uses in medicine and perfumery, but the seventeen-century housewife grew them for many purposes, from flavouring food to scenting a room, chasing away insects or encouraging the much-loved bees, stuffed into a pomander to ward off infections (lockdown precautions maybe?), and most important of all as remedies for illness and disease and household accidents, in families who could not afford the fees of a learned physician or the cost of expensive medicaments from the pharmacy.

The posh folk who escaped from the murk and gloom of the overcrowded city of London to the fresh air and green fields of Hackney owned parkland and big formal gardens with fruit trees and always a well-stocked herb garden. Thomas Cromwell grabbed a massive property in Clapton and converted it into a summer residence fit for a king; his adopted son Raf Sadler built himself a fine modern home, Brick House, now Sutton House, with its garden and orchards. It’s difficult to imagine, given current levels of air pollution in the area, that this very spot was renowned for its healthy atmosphere and open spaces, rural bliss only a short journey from town. Just a step up Mare Street were the broad acres of the manor house attached to the church, where the comfortably prosperous were competing for space to develop old fashioned properties while the less well off lived a more humdrum existence. Sound familiar? Hackney’s capacity to reinvent itself goes back a long way. Market gardens, farms and aristocratic palaces existed side-by-side in the fields and meadows between the little villages of Hoxton, Shoreditch, Dalston, retaining patches of wild and productive greenery, to eat or just enjoy.

The cultivation of vegetables, especially salads, was becoming fashionable in England after years of being dismissed as mere animal food, so when Giacomo Castelvetro found himself exiled from Venice and in need of protection he shrewdly turned to Lucy Harington, Duchess of Bedford, a keen gardener and cultivated patron of the arts, who would have been flattered to be addressed in Italian, in his 1614 book, The Fruit, Herbs & Vegetables of Italy. But the brilliant charismatic Lucy was in 1612 deeply in debt and could not help Giacomo, who died four years later in poverty.

Nobody could have imagined Giacomo Castelvetro to be a spy. The sprightly charming elderly man, hurrying briskly between publishing house and printing office, carrying untidy bundles of proofs and manuscripts, but always ready to stop at the Rialto bridge to peer down at the fish market, or sample the first of the early spring artichokes, and later the plump spears of asparagus from the lagoon islands, or ogle the ladies behind their screens of climbing beans planted in window boxes, did not seem in any way furtive or conspiratorial. A distinguished editor and scholar, Castelvetro was widely travelled, attended the major book fairs, and could boast of having taught the king of Denmark how to propagate fruit trees in his garden, and acted as Italian tutor to James I when he was king of Scotland. So when the Roman Catholic Inquisition eventually caught up with Castelvetro and imprisoned him under the leaden roofs of the notorious piombi, the Venetian state prison, killingly hot in summer and freezing in winter, this connection was exploited by Dudley Carleton, British ambassador in Venice, a clever ambitious young diplomat who rushed to Castelvetro’s lodgings and removed stacks of incriminating documents, then made an international incident of the event, claimed immunity for him as a servant of the Protestant king of England, freeing Giacomo and at the same time winning himself a knighthood and promotion. Castelvetro ended up in England, where he hoped to exploit the new enthusiasm for Italian culture, salads and vegetables in particular. He might not have got to Hackney, for Lucy’s estate was in Twickenham, but his message: ‘Eat more fruit and vegetables, less meat and sugar’ is as urgent now as it was then. And lemons and fresh herbs are happy helpers in our changing ways.

As for being a spy – who knows? More next month.