Over-medicalised child prescribed fentanyl for six years from age five

The case of Child A, prescribed powerful opioid painkillers for six years without any professional oversight of their pain management, “outlines important messages for safeguarding professionals”, according to local safeguarding chief Jim Gamble.

A serious case review by independent reviewer Sarah Baker for the City & Hackney Safeguarding Children Partnership (CHSCP) found that Child A was the subject of “over-medicalisation”, with questions remaining over whether multiple interventions made to address symptoms over their life were needed.

According to the report, Child A, who was weaned off opioid dependency at the age of 11, has been identified as one of several children as part of a review within the paediatric gastroenterology department of a hospital unnamed in the report, which explored how some child patients may have “received inappropriate diagnoses, uncritical long-term treatment and a sub-optimal level of care.”

Jim Gamble, the Independent Child Safeguarding Commissioner of the CHSCP, said: “The serious case review concerning Child A speaks for itself. This highly challenging case outlines important messages for safeguarding professionals who are working with disabled children or those who have complex health needs.

“The CHSCP fully accepts the findings and recommendations made by the independent reviewer and will continue to oversee the programme of work to implement identified improvements.”

Baker’s review makes a number of recommendations, including calling upon the clinical commissioning group for the borough to review the availability of chronic pain services for children, after finding that the lack of a local chronic pain team contributed to inadequate monitoring and supervision of long-term medication for Child A.

Born prematurely, Child A was diagnosed with an inflammatory bowel condition common in premature babies, and the first year of their life was marked by concerns over feeding, weight gain, constipation, excessive crying and developmental progress.

This was also the year, according to the report, which saw the beginnings of the “overmedicalisation” of the child, which found limited communication between the services with which the family were in contact, resulting in Child A seeming to become “lost in a medical intervention model” in the first year of their life.

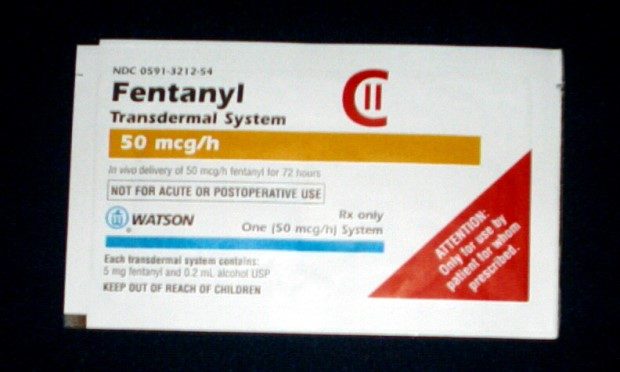

After a long and difficult hospital admission for the insertion of a feeding tube following poor weight gain when Child A was five, they were prescribed fentanyl when they were still perceived to be experiencing significant pain.

No professional oversaw the child’s pain management or the impact of long-term opioid use on their health and daily life over the next six years, the review found.

The child went on to experience significant side effects of fentanyl, which were then compounded by further prescriptions of the drug, which studies have found to be up to 100 times more potent than morphine.

The report is clear that children should not be discharged home on long-term opioids except in the case of palliative care.

The absence of a lead coordinating professional led to Child A’s parents being “inappropriately” left with the responsibility to pass communications and information between practitioners, according to the report, which was told by the child’s mother and father that: “They felt psychologically dependent on the Fentanyl as it meant they could do something about the pain. As a parent you

don’t question you just do it.”

The child’s parents told the review that they had “no idea” that fentanyl was in fact making their child’s pain worse, with wider symptoms of sickness, headaches and abdominal pain potentially caused by the drug.

The report also paints a picture of practitioners “insufficiently challenging and escalating their concerns” about Child A’s situation; some professionals believed that they did not need to explain to the family what services were available due to the parents’ professional background.

Escalation to children’s social care was reported to have been inhibited by “nervousness” amongst professionals caused by the child’s father’s professional experience (not expanded upon in the report), with some saying that “because of his background, they found it difficult to believe there could be any child safeguarding concerns.”

Professionals also reported that Child A’s mother’s articulacy and assertiveness “impacted impacted on their ability to respond to Child A, properly establish views, focus on needs and challenge parental accounts.”

The report also states that hierarchies within the world of medicine prevented professionals escalating their concerns further, with both the child’s GP and community nurses being concerned at their use of opiates but deferring to prescriptions filled out by a specialist. These concerns were raised when the child was eight, by which time Child A was totally reliant on a wheelchair.

The report adds: “Ultimately, it may also have been easier for health practitioners to medicalise Child A as this was known territory for them. This approach is unhelpful and potentially harmful for both the child and the parent/carer.

“As part of the internal review of the paediatric gastroenterology department, a number of other children were identified who were also given an unsubstantiated diagnosis, experienced a lack of regular review and were receiving ongoing medical interventions and treatment.”

Child A continued to take Fentanyl for pain management through patches and a lozenge through the ages of nine and ten, at which time they were reported to be “totally reliant on mother for all aspects of physical care.”

Baker’s report also notes a lack of evidence of any discussion around Child A’s mother’s own use of opioids for pain management and “the impact that this might have had on her parenting capacity of Child A or the family’s views about their use.”

Having been lost in a medical intervention model from an early age, the review also finds Child A becoming lost in the education system, with no reviews held on their educational progress for a number of years.

Child A switched from school to home tutoring at age seven, at the same time as which reforms to special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) provision in 2014 reorganised local educational services.

No reviews were received on educational progress for years as a result, with their former school still formally recording them as a pupil, leading to an assumption that the school was responsible for the child’s annual reviews, which did not take place for four years.

Following concerns mounting over Child A’s use of fentanyl, they were admitted to hospital in 2017 to wean them off the drug, which was successful. Intensive physiotherapy was also begun to help them begin walking again, and for occupational therapy focusing on their avoidance or fear of eating, drinking, or accepting sensation in or around the mouth.

A referral was then made to children’s social care, with a hypothesis being considered at this point of fabricated or induced illness (FII), otherwise known as Munchausen’s syndrome by proxy, a rare form of child abuse in which symptoms of illness in a child are exaggerated or deliberately caused by a parent or carer.

FII was not substantiated following the referral, with the report noting that the reported symptoms of Child A were responded to “without any objective assessment by health professionals,” leading to unnecessary and inappropriate medical intervention.

Baker’s report adds: “From a medical perspective, accepting that treatment may not have been necessary may be difficult for professionals to come to terms with. There is an underlying question about how easy it would be for professionals to say, ‘I don’t know’ and not provide treatment. How would the medical world and society view and accept this position?

“There is also a genuine question about the costs of overdiagnosis and the need to develop further guidance on the demedicalisation of care.

“There has also been professional resistance to recognising the clustering of such cases around particular paediatric units (Child A was one of twelve children identified by the hospital) and particular new diagnostic labels (Child A was misdiagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome hypermobility type).

“There is a need for health services to have in place clear systems where such clusters or routine / frequent misdiagnoses can be promptly identified.”

Key to Baker’s findings is the act that that the voice of Child A was “not consistently listened to,” with professionals deferring to the child’s mother’s voice instead.

The review’s recommendations include for a wide-scale promotion of the voice of the child to take place through the CHSCP, to ensure the importance of communicating with all children and young people, as well as for local health providers to audit their paediatric community and inpatient records to ensure children have been involved, in an age appropriate way, at each stage of their care planning, with their views listened to and considered.

Cllr Anntoinette Bramble, Cabinet Member for Education, Young People and Children’s Social Care, said: “This was an extremely complex case involving a number of different agencies.

“Whilst the focus of the report is mainly upon the response to Child A’s health needs, it rightly identifies where our historic practise could and should have been better.

“We accept all the findings and recommendations made in the review. And we wish Child A all the best for their future.”

You can read the full serious case review into Child A’s case here.