Reflections on 2020

At the beginning of 2020, as we emerged from winter, we slowly began to notice the news coverage of the eternally fruitless Brexit negotiations had given way to something else entirely.

Increasingly perplexed and anxious scientists and medics lined up to speak of an invisible assailant which was edging ever closer. This assailant, they said, was unconcerned with the niceties of queuing up at passport control or politely presenting itself at the Customs Office before leaving the airport. Its only intention was to find its way to our vital organs and to slowly destroy us from the inside until even a singular breath became an impossibility.

At first, many of us struggled to know what to make of this troubling news. Some tried to continue under a veneer of normalcy, but as the threat loomed nearer we each became more tense and confused.

This year, everyone had a moment when they knew everything had changed, where in the blink of an eye there was a new understanding that we were entering a liminal space, where the old world gradually disintegrated behind us and we were left gaping at an unknown future.

During my teenage years my dad, who was raised in Uganda and had spent a considerable chunk of his own childhood under the reign of Idi Amin and a cycle of coups, uprisings and the start of the Aids epidemic, would tell me in his home nation everything could change in a brief second.

As my dad would repeat tales about his small Central African country, half listening I naively assumed his reality would never apply to my life. Maybe this was down to my own personal arrogance or perhaps because – despite my family story being borne of the vestiges of empire – growing up in London I was also not impervious to the national exceptionalism that legacies of colonial supremacy have inscribed on our national character. It was most probably a combination of both these things.

There is no doubt that I have had episodes of personal trauma and loss but such a sudden, profound unravelling of the entire state was previously unfathomable to me.

My moment of recognition came during a pre-lockdown walk in March to my local Tesco. It left the thread of false security I had been dangling on forever ruptured.

I have been visiting this Tesco for as long as I can remember and recall as a child disinterestedly trailing behind my mum whilst she loaded the weekly shop into the trolley. As we left, I would impatiently wait as she invariably noticed someone she knew and stopped to regale them of the intricacies of her life since she had last seen them.

Now, as I approached Tesco, that old familiarity was gone and I instead saw huge queues snaking outside and security guards stationed ominously at the entrance. This supermarket, which had once symbolised comfortable certainty and unappreciated abundance, was now a site of insecurity.

To my consternation, the scene was replicated all the way down the road. Every food shop had its own long queue outside and staff guarding the doors. In that one vision I realised things were never going to be as they had always been before.

Unnerved by the sight at Tesco, I walked instead to a convenience shop further down, the only store which looked promising enough to bear any fruits. After waiting outside for more than fifteen minutes in a large crowd, I was finally allowed in. I found myself looking hopelessly at the near empty shelves as I silently cursed the people who had got there first. Emerging from the shop with canned chickpeas and rice, I hurried home carrying my purchases like precious gifts.

Photograph: Polly Braden

A few days later, Boris Johnson appeared on our screens speaking of a national lockdown. The scientists said that for months Britain would need to hibernate as this would be our most effective weapon against the enemy.

In hospitals, countless loved ones lay alone in intensive care whilst, further down the corridors, new life was breathed into grandchildren who were destined to first meet doting grandparents, not by way of a delicate embrace, but through a window.

At home, many families found themselves thrown into an enforced, inescapable domesticity. Couples who, for years, had said no more to each other than two hikers passing at the summit of a famous mountain, suddenly found every minute was entwined with the presence of the other. Those idiosyncrasies which, at one time or another, had felt so cherished acquired a new exquisite agony now that external intermediaries could no longer conceal the fact that the person who ate dinner opposite every evening was actually a stranger in disguise.

Other couples found the lockdown revived their love, and their relationships developed new dimensions now that outside distractions were forbidden. Imprisoned in their homes, they found themselves rediscovering the contours of each other’s bodies, which for so long had eluded them in a hurricane of endless work commitments and social engagements.

Some single people wondered when they would next be able to venture out and renew the search for that someone, recalling the rush of excitement that comes with being on a first date when two pairs of eyes interlock, triggering that tantalising tremor of energy we colloquially call ‘chemistry’.

Through all the tumult a silent army continued on. The care worker still found an extra moment for the dementia patient whose children could no longer visit and who, despite having forgotten so much, could still recollect in the most intricate detail the terror of being a six-year-old boy who had never left his mother’s side, now alone on a train bound to Devon, having been evacuated from London.

The teachers still toiled around the clock, planning and delivering online lessons with the same care and diligence but now, with schools closed, carrying the added burden of worrying even more about that child with bloodshot eyes who sat at the back in sullen silence and always looked hungry.

And of course the nurses, the doctors, the paramedics still dutifully cared for the sick despite having their own families and not knowing whether they might themselves become infected.

The pandemic turned so many fissures in the flooring of our society into gaping potholes. The families whose lives had already been broken open by separation through the care system, the mental health system and the immigration system were now more invisible than ever. The boss who degraded their workers, sometimes out of a burning desire for superiority and sometimes out of a furious bitterness and sadness with their own life, now felt more emboldened than ever because subconsciously they knew, and their workers knew, they each relied on that monthly pay cheque more than ever.

And what of those unable to work or those working long hours but still not paid enough to feed their families? Whilst our government obfuscated and delayed, every day people recognised their neighbours’ difficulties.

In Cazenove, over 200 volunteers and local businesses helped by working to ensure no-one in the ward went hungry in an initiative mirrored all over Hackney, although underlying these machinations was the burning question ‘why foodbanks in the fifth richest country in the world’.

Before he was murdered in a drive-by shooting at the age of 25, the rapper Tupac Shakur observed in the 1993 single ‘Keep Ya Head Up’: “They got money for war but can’t feed the poor.” In all the time that has since passed, so little has fundamentally changed.

In the absence of humans crushing it underfoot, nature was left to blossom. Across our city, birdsong filled the air, no longer competing with the eternal din of cars. For the first time in our life we looked up to the heavens and the lines vomited out by planes’ engines had completely vanished.

London, one of the world’s great cities, was a metropolis abandoned. On a walk during lockdown I found myself in Brick Lane and was stunned by the absolute desolation. All my life I have passed the curry houses, bagel shops and vintage outlets, ever teeming with activity, to now find the only movement from living things came from those pigeons still circling greedily for scraps, presumably confounded by the utter absence of humans.

Then lockdown restrictions eased and, as a friend mischievously noted, big groups were fine so long as a cash machine was present.

In summer, the parks overflowed with a constellation of different groups. In our green spaces, old men played cards, poised with the same dignity and majesty as any Knight of Camelot at the Round Table, whilst toddlers erratically thundered past. Later at night, under cover of darkness, our parks hosted riotous parties attended by young graduates who had just moved to the capital in search of work, along with local teenagers.

Whilst humanity tried to contain the threat, we had to confront the uncomfortable reality that we were battling a zoonotic disease which has risen from conditions produced by human exploitation of the natural world. The importance of revaluating humanity’s relationship with other living beings could not have been clearer.

Photograph: Friends of the Happy Man Tree

A local illustration of this occurred earlier this year when one of Hackney’s oldest residents and a vital piece of the borough’s tapestry, the Happy Man Tree, faced an existential threat to its survival. There was no place for the 150-year-old London plane in the next phase of the regeneration of Woodberry Down Estate.

Residents responded to the news with love, outstretching their arms around the Happy Man and rushing to its defence. Their tireless campaign had some success, with the Happy Man gaining national recognition when it won the Woodland Trust’s Tree of the Year award, but unfortunately its felling looks set to take place very soon.

It is said in times of great social upheaval that creativity blossoms, and so it was no surprise in Hackney, long a cradle of radicalism and dynamism, that art continued to flourish. In a period of such immense bereavement, across the landscape of our borough, art was erected to commemorate the lives of those lost.

On Clapton Common, the ‘Memori-Wall’ was established, partially as a response to the restrictions on communal gatherings at funerals, and residents were invited to memorialise their lost loved ones.

In September, Hackney resident and world famous artist Stik unveiled his Holding Hands sculpture at Hoxton Square – the two figures turned in different directions with hands intertwined representing friendship and solidarity. The unwrapping of the statue was particularly poignant at a time when Covid-19 has prohibited holding hands and close contact. However, rather than a reminder of the painful absence of human warmth, the sculpture has served as a monument to hope, quietly reassuring us there will come a time, once again, where we can hold hands without fear.

Over in Stoke Newington, another artwork was erected to pay homage to the borough’s revolutionary ties with the unveiling of a statue for 18th-century political thinker Mary Wollstonecraft. The statue stands in Newington Green, opposite the Unitarian Church where Mary herself spent time and where she dreamed of remodelling the world anew. Although Mary’s dreams are yet to be fully realised, the statue, like Mary herself during her lifetime, divided opinion and provoked an important conversation about gendered representation in art – no doubt she would be proud of that.

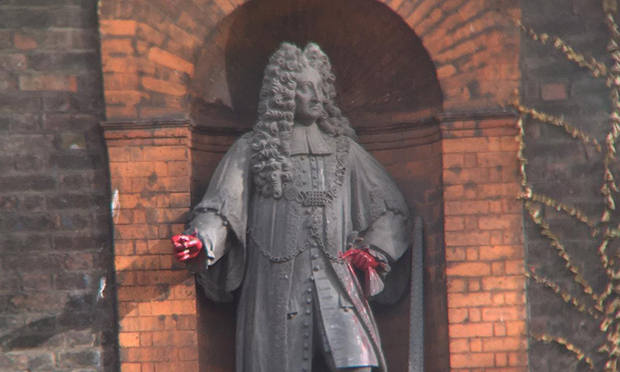

Elsewhere, campaigns sprung up to remove statues of those with far less admirable historical records during a long overdue racial reckoning.

This year, Black Lives Matter protests erupted across the globe in response to yet another video of yet another Black man, whose mere existence in America was a crime grave enough for the police to murder him, and highlighted the extent of the racial inequity not only there but also here in Britain. The movement has begun a conversation which for so long in Britain has been swept under the carpet, a discussion about our present and our history and who has the power to tell the story of our conflictual past.

With the interconnected nature of our world, social justice movements rarely stay within the borders of the nation states which give rise to them. This means a movement which started at the University of Cape Town to topple a statue of the colonialist Cecil Rhodes spread to the cobbled lanes of Oxford and then across the UK, eventually finding expression in a local campaign to remove the statue of slaver Robert Geffrye from the Museum of the Home.

I remember being a six- or seven-year-old on school trips walking through the Museum of the Home (then the Geffrye Museum) and marveling at the many sumptuous rooms and galleries. Of course, back then I was unaware that the man whose statue was proudly displayed in the niche above the front door and elevated on high had profited from the sale of human beings who looked like me, who were shipped across the Atlantic never to return to the land of their birth.

The lockdown threw into even sharper focus the reality of the inequalities in our society and demonstrated that basic necessities like adequate shelter, though essential to social distancing, were unobtainable for many people.

To tackle this unfairness we have seen campaigns in the borough for more equitable housing and promoting tenants’ rights ramp up their efforts. The Morning Lane People’s Space Campaign group (MOPS) is one such initiative, formed in response to plans to turn the Morning Lane Tesco into a retail, office and residential complex with no social housing. The group is calling for at least 50 per cent council housing on the site as well as greater dialogue between the developers and the community.

MOPS, and groups like it, make these demands because they know the brand of predatory capitalism purveyed by many developers can only ultimately lead to the displacement of local communities that cannot afford the extortionate private rents but who have only ever known and called Hackney home.

Every weekend, MOPS would set up a small, rickety stall outside Tesco and, in spite of the often miserable weather, would collate the views of local residents on the future of the site. One Saturday I joined them and everyone I spoke to was unanimous that, whatever development appeared on the site, it had to work for the whole community.

Photograph: Harry Mitchell

The future of the Morning Lane site remains unclear but over in north Hackney, a campaign by Somerford Grove Renters highlighted just how exploitative the private renting sector can be towards tenants. In response to asking for moderate rent reductions during lockdown, when many people were having to self-isolate and losing work, the renters claim they were targeted by their landlord after inexplicably receiving eviction notices. Faced with this injustice, the renters united and fought back, ultimately winning their campaign when their eviction notices were withdrawn.

This year, everyone found their own ways to cope, whether through baking hundreds of loaves of banana bread, immersing themselves in video games or finally reading all the classics they have been pretending to be an expert on for the past 20 years.

For me, I unexpectedly found myself, after a self-imposed exile of more than ten years, standing in a pew at Catholic mass, masked up and socially distanced from fellow congregants. A thousand childhood memories flooded into my mind of First Holy Communion ceremonies, baptisms and family funerals. I marveled at how, after all this time, it was still so easy to recall the order of the mass, the words of The Nicene Creed and the other prayers as though I had last recited them only yesterday. In a time of turmoil, it offered a connection with a power greater than me and though I can’t say with certainty what pulled me back there, what I do know is the pandemic has definitely made many of us reappraise our lives and what we consider important, which means we can end up travelling in unpredictable directions.

We are ending the year, in Hackney and around the world, in the hope of new beginnings with the roll-out of the vaccination programme. At few other points in history have our common humanity and vulnerability been more apparent than in 2020.

Despite the arrival of the vaccine, the pandemic has created severe damage, both economically and socially, with many hard days ahead. Whatever we next face, I try to find solace in difficult times by thinking of the fable of the ancient Persian philosopher, who, in response to his King’s request to encapsulate in a single phrase a fundamental truth about human life that would hold for all time, uttered: “This too shall pass.”