Exploding grannies and sleepy pears

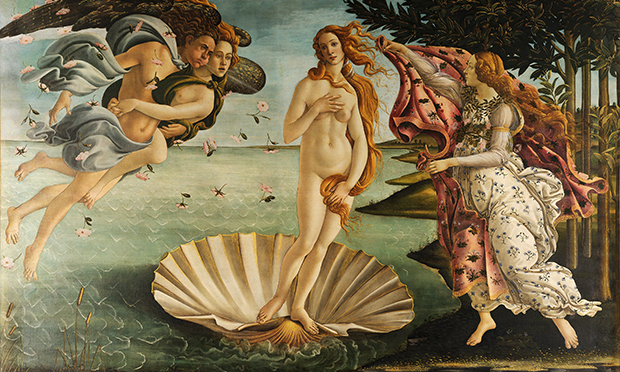

Most Italians enjoy legends, sayings, and proverbs about their food, which don’t have to be believable or accurate, they survive as a way of showing loyalty and affection for a locality and its cooking. Like the one about Venus’s tummy button, which is what the tortellini of Modena and Bologna look like, when made by hand in the kitchens of the towns and villages of Emilia-Romagna in northern Italy.

Legends around these tiny little gems of stuffed pasta go back to the Middle Ages and one of them got immortalised in 1614 in a comic poem La Secchia Rapita by Alessandro Tassoni, all about how the rival armies of Modena and Bologna got into a nasty fight over a stolen wooden bucket.

The story took place in a small town, Castelfranco, on the border between those two rival territories, where the gods Venus, Mars and Bacchus were staying at the inn, to oversee the conflict. The lecherous landlord, gazing through the keyhole of their room, was so entranced by the charms of the goddess that he rushed back to his kitchen to make tortellini, a tribute to her perfectly formed umbilical.

This column has sat with the grannies at a scrubbed wooden kitchen table only a few kilometres from the theft of the bucket, learning the secrets of the ingredients for the filling, and how to place, seal in, fold over and press into shape these exquisite morsels.

But the grannies like the myths have to be exploded from time to time; we need to remember that tortellini in brodo was a luxury festive dish, made only a few times each year, for special occasions like a wedding or Christmas Eve, not something you can eat twice daily on a tourist menu.

The rosy-cheeked smiling granny with sprigged apron and hair in a bun is a myth, and not a comfortable one, as Karima Moyer Nocchi has shown in Chewing the Fat, her interviews with a wide range of old ladies of that generation, whose lives were hard and memories far from rose-tinted.

A new generation of Italian historians are thoughtfully questioning some of the soft-centred assumptions of sayings used to enhance tourist gastronomy, or puzzle the sociologists.

An enigmatic proverb that can mean almost anything has been gone into with almost excessive zeal by Massimo Montanari: ‘Al contadino non fa sapere quanto buono e il formaggio con le pere’, or ‘Never let the peasant know, how well with cheese a pear can go.’ A saying that can be interpreted in terms of class warfare, or economic repression.

A perfect ripe pear along with an exquisite fresh young cheese are ephemeral treats that only the privileged can afford, a peasant who aspires to such luxuries is a serious threat to the social order.

The system of landholding known as mezzadria left those who worked the land, as tenant farmers or agricultural workers, unable to afford the luxuries they produced, oppressed as they were by landowners and their beady-eyed overseers, monitoring both the produce and income of farms, to squeeze out the last drop of profit. Well in spite of this the contadino had the last word, as Montanari reveals on the ultimate page: ‘Al contadino non fa sapere, quanto e buono il formaggio con le pere. Ma il contadino, che non era coglione, lo sapeva prima del padrone’. ‘The wily peasant, never at a loss, knew this long before his boss.’

Pears and cheese were enjoyed in Madrid in the 18th century, we see them together in many of the still life paintings of Meléndez, where one can enjoy the way each work of his depicts, with clarity and restraint, a recipe or the components of a meal or a snack. There are pears and cheeses in various combinations, showing how we too can eat pears with parmesan, or a softer goat’s cheese, or even a light cream cheese, and Meléndez indicates the membrillo, in its rectangular wooden boxes, that also enhance the combination of slightly acidic fruit and creaminess.

They say that there are only a few hours of perfection in the life of a pear; early on it is woody and tasteless, and after that all ‘sleepy’ and mushy. This is true for some pears, and like so much summer fruit, the commercial constraints of getting fruit looking fresh and alluring at point of sale means they are picked long before ripeness, and what with long journeys in refrigerated transport, display in cooled cabinets, we get rock-hard beauties that drift into senescence without ever enjoying maturity.

This is very depressing, but a few weeks ago customers at Gallo Nero were almost blown off their feet by waves of perfume from a tray of ripe peaches. Human error (not Michele’s) must have been to blame, as the happy customers snatched them all up and fled into the night.

When the Medici rulers of Florence in the 17th century employed Giovanna Garzoni to paint still lifes of the fruit and products of Tuscany, it was not just as patrons of the arts, but as promotion of Florence’s botanical studies and local agriculture.

The amazing group portraits of fruit by Bartolomeo Bimbi were commissioned for the same purpose, and hung on the walls of the villas the Medici built in the countryside around Florence (to be seen today at the Museum of Still Lifes at Poggio a Caiani), where gardeners and botanists tended specimens from all over the known world, and worked on the development of new versions of existing species.

The vast paintings of cherries are a happy reminder of fruit that don’t mind the cold, which is perhaps why Cardinal Wolsey toyed with a dish of them in Wolf Hall, as described by Hilary Mantel: ‘In the case of his man Cromwell, the cardinal has two jokes, which sometimes unite to form one. The first is that he walks in demanding cherries in April and lettuce in December. The other is that he goes about the countryside committing outrages, and charging them to the cardinal’s accounts.’