Tamsin Ssembajjo Quigley: ‘The maker movement has never been more important’

Photograph: Gascoyne Residents’ Association

In the Gascoyne Community Centre, a building sitting in a tranquil location on the periphery of Well Street Common, a group of people encompassing all ages and cultural backgrounds diligently work.

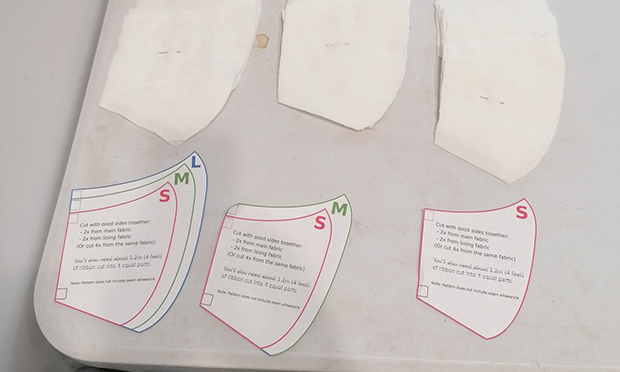

Members of the group are alternatively stationed on sewing machines, cutting cloth and measuring materials.

Using a vibrant assortment of patterned fabrics, from psychedelic geometric designs to traditional West African print, the group manufactures face masks for Gascoyne Estate residents.

At the entrance of the community centre, a range of completed masks are proudly displayed on a table.

There is a mask for every preference and taste. A mask depicting characters from the 1970s Japanese cartoon series The Ultraman lies alongside another more muted creation in tasteful blossom pink.

The masks are made from repurposed materials which evoke untold stories from past lives as intriguing and complicated as any from the population of Hackney itself.

At the start of the pandemic, Alana Heaney, chair of the Gascoyne Residents’ Association, reflected on how she could utilise her skills to contribute to the fight against coronavirus.

Photograph: Gascoyne Residents’ Association

Alana told the Citizen that growing up in Ireland as a child she had been taught to sew in a traditional manner by her grandmother. She decided she would harness this ability, previously a part-time hobby, to construct face masks for her friends and all residents of the Gascoyne Estate.

Prior to beginning her work, Alana was confronted with two critical challenges – all the fabric shops were closed and she had never made a face mask before.

Determined not to let these obstacles impede her, Alana educated herself about prototypes of face masks by reading World Health Organisation guidance and by watching numerous YouTube videos.

In the absence of being able to procure shop-bought cloth, she dug out fabrics she had previously employed as bunting for a community event to use for the masks.

At the start of lockdown, Alana says she would sew and construct the masks in her own home. After a while, other residents who also possessed sewing expertise began to collaborate with her and since then the group have relocated from their individual living rooms to a shared space in the Gascoyne Community Centre.

Early on, they realised they needed to establish a reliable supply chain to support their machinations. They liaised with Thingy Café in Hackney Wick, which now provides them with daily donations of Tetra PAK bottle tops, while residents regularly donate their own unused cloth.

Photograph: Gascoyne Residents’ Association

Members of Covid-19 mutual aid groups, local youth clubs and Gascoyne Estate residents have all contributed sewing machines to the effort.

At time of writing, Alana estimates the group has distributed over 300 masks and counting.

The Gascoyne mask-making group is a microcosm of the resourcefulness and creativity that have been blossoming in communities across the country during the pandemic.

Collectively, these groups form part of a wider manufacturing tradition known as the ‘maker movement’. Although there is no universal definition, this is a loose term for a phenomena that can broadly be defined as designers – some self-taught, others formally trained – who use digital and non-digital fabrication technologies to create products for the social benefit of communities rather than for financial gain.

If the history of humanity was encapsulated in a single car journey, the road map would be punctuated with unexpected pot holes and death-defying turns to symbolise the myriad wars, famines and plagues which have confronted us over the millennia.

Essentially, our past would resemble a version of the notorious Old Yungas Road, famously branded the most dangerous road in the world.

For all humanity’s undesirable character traits, our pragmatism and indomitable will to survive have seen us through numerous existential threats. The Maker Movement speaks to this fundamental aspect of being human. When we are confronted with a problem we scrabble around, gather available resources and use our ingenuity to assemble tools to try to overcome.

Over in north London, another maker has also spent the past few months harnessing their skills and expertise in the battle against Covid-19.

Lucia Corsini has been an advocate for the maker movement for a number of years, having undertaken detailed research into the manifold possibilities it offers.

At the start of the year, Lucia was based in Cambridge, putting the finishing touches on her PhD thesis, which focused on exploring how digital fabrication and makerspaces can help solve humanitarian and development problems.

When the pandemic arrived, she immediately recognised the maker movement’s ability to respond to communities’ needs, particularly given preexisting international production lines were unlikely to have the capacity or resilience to cope with the exponential global increase in demand for PPE and ventilators.

Lucia, who spoke to the Citizen in a personal capacity, said whilst traditionally the maker movement has been concerned with design and prototyping, the pandemic has ushered in a real paradigm shift in prevailing academic and industry assumptions about its potential to deliver manufactured products.

She said: “Until now, the maker community has been largely seen as an unprofessional, hobbyist movement. This pandemic has put a spot light on the latent innovation potential of our communities, and shown how makers can contribute valuable solutions to pressing problems.”

Opening up a national dialogue about the possibilities of the maker movement is particularly vital given that, on many occasions during the pandemic, it was makers like the Gascoyne Residents Association who mobilised and distributed resources to communities far more rapidly than our government.

Lucia welcomes the maker movement’s egalitarian nature and focus on reciprocity between makers, adding: “The amazing thing about the maker community is that anyone can join. The movement is all about sharing and collaboratively designing solutions.”

For those interested in getting involved themselves, Lucia says there are plenty of opportunities out there.

“In the UK, there are different initiatives that you might be interested in depending on what skills and resources you have available,” she explained.

“For example, 3D Crowd UK coordinates volunteers with 3D printers to make face shields. For the Love of Scrubs is a nationwide group that sews hospital scrubs that you connect with on Facebook. Ragmask is a website where you can download designs for sewing your own face masks.”

The news this week that Antarctica’s colossal Thwaites Glacier is melting serves as another reminder that our world remains perilously close to the precipice of environmental disaster.

The glacier has famously been termed ‘The Doomsday Glacier’ because of the catastrophic harm its demise could have on rising sea levels.

Lucia believes that, with the right approach, the maker movement has the capacity to offer serious alternatives to the industrial production lines which have accelerated climate breakdown.

She said: “The maker movement creates the potential for more sustainable forms of production and consumption. Making is intrinsically connected with DIY and hacking culture, which signals a move towards fixing and repairing items instead of sending them to landfill.

“Makerspaces also open up the possibility for local and distributed production. By sharing resources and making things locally, you can reduce supply chains and eliminate waste by making things on-demand.”

Lucia is now a Research Associate at the Institute for Manufacturing in the Engineering Department of University of Cambridge, and in the coming months, alongside partners at the Centre for Global Equality at Cambridge, the Bahir Dar Institute of Technology and Malawi Polytechnic, she hopes to use 3D printing and laser cutting to locally produce face masks and face shields to tackle the spread of Covid-19.

Lucia and her colleagues will be working to develop a blueprint for how to successfully deploy digital fabrication in a crisis, in regions with limited manufacturing infrastructure.

Whether at home or abroad, we all owe a great deal to makers like the Gascoyne Residents’ Association and Lucia and her colleagues, who are providing us with vital protections against coronavirus that we would not necessarily otherwise possess.

As our country hurtles towards a post-Brexit future, where established trading arrangements may end up being completely reconfigured and the pandemic places increasing strain on the world’s supply chains, the importance of the maker movement has never been more apparent.