‘Goodness had nothing to with it’

This column, head down in a bowl of pineapple, pork, and chipotle in adobe, totally missed out on Veganuary.

Too late now to catch up, but glad to remember how it is so often vegetables that make a dish tasty and healthy, and glad too to escape from rigid doctrines and passionate prohibitions associated with vegetable and meat-eating. We can simply enjoy all of them, grown and cooked with care, as part of a varied diet, remembering the wise words of Michael Pollan, ‘Eat food. Not too much. Mainly plants.’ in his book In Defence of Food.

When serious vegans can bring themselves to buy a product recently promoted by a major food supplier as ‘vegan sausage roll’, the mind boggles. Sausage? If you object to killing and eating a pig, why name the vegan alternative, constructed from a substitute made with soy beans and lots of dubious additives, after a product made from stuffing the flesh of the murdered animal into its own guts? What’s in this for us?

It’s a nice little earner for the international food industries, millions of dollars a year, but as Mae West said in a different context: “Goodness had nothing to do with it.”

In the 1930s film Night After Night, the diva shrugged off her mink stole, revealing a glittering voluptuous corsage, at which the hat-check girl exclaimed: “Goodness, what lovely diamonds!” “Goodness had nothing to do with it, dearie…” drawled Miss West as she sashayed off to the gaming tables. She had a point. Goodness is what’s being cynically offered up by some wholesale industrial manufacturers of vegan foods. Nothing to do with the sincere ideals of conviction vegans, the name is now promoted as a brand, so that we are all encouraged to buy stuff that calls itself vegan, happy that it’s cheaper than meat and ever so tasty, and comes with a built in feel-good factor, allowing us all to eat ‘vegan’ in a moral vacuum.

But being just a little bit vegan is like being only just a little bit pregnant. Think it through. Throughout history the less well-off had to survive on vegetables, pulses and grains, and meat was more of an expensive condiment or a rare luxury than something you agonised over eating or giving up.

Prehistoric man might have first eaten meat left over from creatures who slaughtered and ate each other, road-kill before roads as it were, and combined this with wild nuts, seeds and berries, before inventing agriculture and animal husbandry. So our complicated relationship with the animal world goes back a long way; early cave art shows how we worshipped wild beasts for their power and beauty, rather than as ingredients.

Inuit art values and placates the spirits of the creatures Eskimos kill in order to survive. The Inuit nations around the North Pole relied almost totally on fish, aquatic animals like seals, and caribou, with a few berries and roots. Fresh fish were frozen and kept in hygienic conditions to use later, or the catch was laid out to dry in the summer, fermenting and rotting away, creating tasty nutrients and vitamins, to freeze during the winter and enjoy as a treat.

Tinned sardines and anchovies remind us of this, and Vietnamese fish sauce, or Indonesian trasi, and the Roman condiment garum, made in vast quantities from the rotting entrails of small fish, were often permitted in a vegetarian diet.

The altar and the slaughter-house were, and are, close in many of the world’s religions. The gods of ancient Mesopotamia were offered a great deal of food and drink, and the lists that survive of slaughtered animals, that the gods did not need for survival, but we humans did, leads historians to conclude that there must have been a trickle-down of food via priests and kings to the rest of the population.

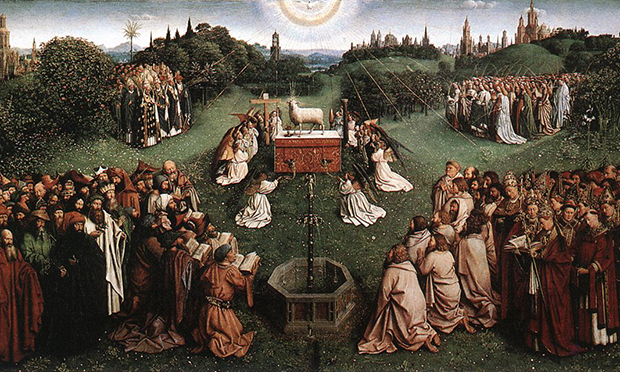

We can see the sacrificial lamb of Christian theology in the recently restored altarpiece in St Bavo’s cathedral in Ghent, painted by the Van Eyck brothers in 1432. The lamb in the centre of a huge scene of worshippers fixes us with a cold reproachful gaze, eyes more human than animal, so disturbing that the painting was soon altered to tone down its unsettling impact.

Later, in 17th-century Portugal, Josefa Obídos gives a sentimental version, with a tethered lamb surrounded by pretty flowers that we can weep over in comfort.

Thanks to the preferences and prohibitions of many races and religions we have a wonderful range of food resources here in Hackney. It’s not the innovative cocktail bars with their sensitive fermentation, or bubble teas, or vegan burgers, but the ordinary food shops and street markets that make cooking and eating so agreeable.

The gentrified foodie scene might have inspired the mini branches of the big supermarkets to stock ras el hanout and harissa, sichuan peppercorns and asafoetida, but the invisible nine tenths of Hackney’s food pyramid is hidden away in the shopping bags of those of us who buy stuff in local shops to take home and cook, and rarely get to spend a week’s housekeeping on a meal for two in our local tapas bar.

The various ethical and ethnic patterns of eating are liberating rather than restrictive, as butchers in Hackney from Meat N16 to the stalls in Ridley Road sell recognisable parts and organs, unlike the supermarkets offering animal protein in clingfilm-wrapped anonymity, reassuringly guilt-free, but leaving you wondering. And the range of fruit and vegetables is enormous, from shoots like summer asparagus to the roots of winter.

Mae West saw us in with her own view of ‘goodness’, and she has the last word: “I never worry about diets. The only carrots that interest me are the numbers of carats you get in a diamond.”