Going Ananas

Image: Fitzwilliam Museum

This column has been inspired by Kaori O’Connor’s Pineapple: A Global History, Reaktion Books, 2013, but as we all know, inspiration is the first step on the slippery downhill road to plagiary and total rip-off, via daylight robbery, so our warmest thanks to Kaori for sharing your enthusiasm with us at the Hackney Citizen, and making the story of the pineapple so enjoyable.

Pineapples probably originated in tropical Central America and spread wherever they could be cultivated with ease. The pendulum swings from a delicious cheap fruit for the masses in tropical climes, to a hard-to-grow indulgence for the wealthy elite in the chill of northern Europe.

It was the canning industry in Hawaii that did the trick – turning a rich man’s luxury fruit into an inexpensive treat for the rest of us.

From 1910 onwards the pineapple plantations in Hawaii filled thousands of tins with perfectly ripe chunks or slices, and steamships delivered them fast and at low cost all over the world. A lovely reversal of the elitist situation where at the height of eighteenth century mania a carefully ripened fruit cost £80 to produce, about £1,890 today.

To recreate in cold grey northern Europe the tropical conditions in which pineapples could grow and ripen involved building hothouses at enormous expense. The Dutch were good at this, so it is not surprising that some of the earliest sightings of pineapples in art were made as early as the 1650s, before the famous picture of his gardener handing a rather wizened little pineapple to king Charles II in his gardens at Dorney Court in Berkshire in 1666.

Little did Frans Post know when he set off for Brazil in 1636 that his adventure would be so short, ending after only seven years. He was commissioned by Johan Maurits, the ruler of Dutch Brazil, newly snatched from the Portuguese in 1637, to record the scenery, people, plants, animals and birds of this exotic new colony.

Post and his colleague Albert Eckhout made sketches and finished paintings, like the above still life of Brazilian fruit, but it was seven years later, when the Portuguese recaptured Brazil, and Maurits’s venture failed, that Frans Post found new clients among the dispossessed settlers back home in Holland. They wanted nostalgia, not scientific accuracy, and the artist dished it up for them, emphasising the blue skies, benign climate and charming countryside, with picturesque farms and docile natives, as in conventional Dutch landscape and genre paintings, although some of these scenes depicted the notorious sugar plantations and factories, manned by African slaves living in appalling conditions – a nice little earner encouraged by Maurits, who imported thousands of them.

Over 100 paintings for this mainly ex-pat market survive, and a surprising number of them show a pineapple in the foreground, portrayed above as a hedgerow fruit, something cheap and cheerful, while back home in Holland it was the most expensive luxury imaginable, but at the same time a symbol of the good life left behind, and for historians an early and accurate depictions of this splendid fruit.

By the 18th century rearing grapes and hothouse fruit became a lucrative branch of horticulture, while growers in Hackney had a nearby market in the City for less prestigious fruit.

The wealthy Dutch merchant and entrepreneur Matthew Decker moved from Broad Street to Richmond, a fashionable country retreat, and there he grew in 1720 what is claimed to be the first pineapple to flourish in England.

A portrait of it can be seen in the exhibition Feast & Fast at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, more than a stone’s throw from Hackney, but well worth a visit, on now until 26 April. Here we can follow the almost absurd trajectory of pineapple as fashion icon, when it was so expensive that even wealthy clients found it less costly, though still expensive, to reproduce the rare and perishable fruit as sugar sculpture or even ice cream, as Ivan Day has shown in a glorious example.

The seriously rich grew their own pineapples, to display as the centrepiece of a posh dinner table, but the aspiring middle classes could also hire one from a confectioner for a few hours, until it perished from over-use.

Photograph: liminside / Reddit

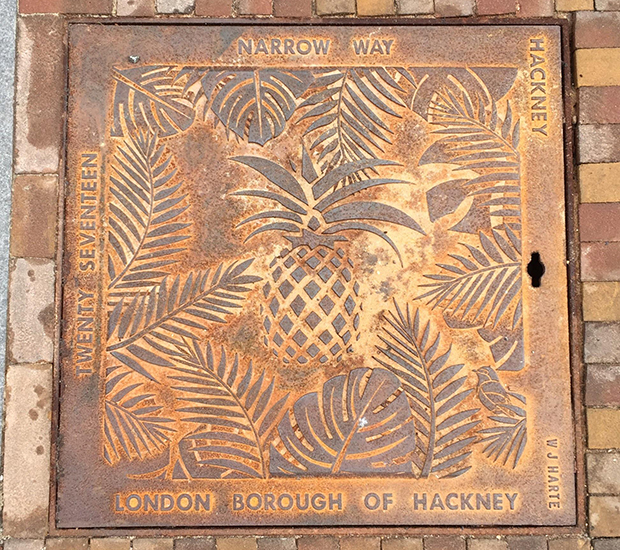

The pineapple was given a longer lease of life in cast iron, where it made a visually pleasing terminal to railings and doorways. Stone sculptured pineapples appeared as architectural follies and fountains, and we have our own manhole cover in Hackney to remind us of its past glories.

Modern publicity in the 1920s spawned a massive pineapple that dominated the Honolulu cannery, over 200 feet above sea level, the biggest in the world, and while in Hawaii we should try Kaori’s traditional recipe for pork spare ribs, with its Japanese and American influences, where the meat is browned in oil before cooking in a slow oven for an hour or so, immersed in a sauce of sake, sugar, rice vinegar, soy sauce, ginger and pineapple juice and fruit.

It is a pleasure to end where we began, with the humble tinned pineapple, despised in pre-war times as cheap and somewhat common, then lusted after when ‘on points’ during wartime rationing – enjoyed with Carnation tinned evaporated milk (bliss!) as a special treat – and now appreciated as a superfood, if you like that kind of thing, with its abundance of vitamins and nutrients.

Hackney might not have the benign climate of Hawaii but it can compete with its pineapple cocktails and spicy dishes, and this almost hedgerow fruit in every food store and market.