Master – An Ainu Story, Sway Gallery, exhibition review: ‘A salutary reminder of the diversity of all identity’

At a time when the UK is wrestling with who we are as a people, the granularity of culture is worth remembering: beneath every seemingly monolithic group lies layer upon layer of diversity, variation and difference.

A new exhibition of photographs at Sway Gallery about the indigenous Ainu people of Japan shows this to be the case even for the reputedly homogeneous Japanese.

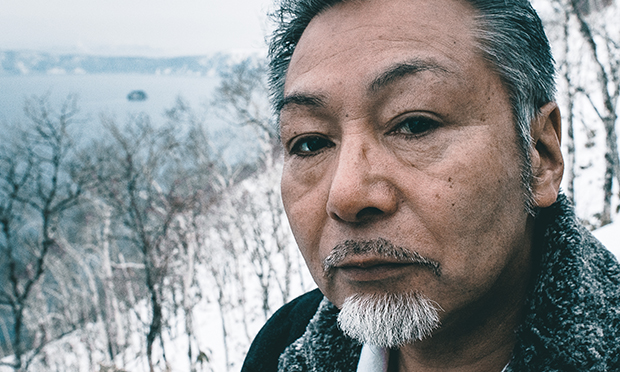

The images by British photographer Adam Isfendiyar depict the Ainu through the story of a single man, restaurant-owner Kenji Matsuda.

Like many in his group, Matsuda suffered discrimination as a child, and his grandmother lived through a period of forced assimilation that started in the 19th century.

Though this people has inhabited the islands of Japan since before the arrival of the ethnic Japanese, the systematic suppression of their culture all but wiped out traces of their heritage.

Gradually in recent decades, the Ainu have been able to piece back together their identity.

A law passed in 1997 recognised them as an ethnic group; a second law in February of this year acknowledged their indigenous status and restored their right to certain traditional cultural practices.

I caught up with Adam Isfendiyar at the gallery and asked him to explain how the project came about.

Having become interested in the Ainu during an eight-year stay in Tokyo, he carried out research in a somewhat circuitous manner: “I bought a book in the market of Ainu tales – it was a kid’s book and my Japanese was at kid’s level. From that book I found out about them.”

He wanted to know more, so he found an Ainu cultural centre in Tokyo which pointed him to a festival where he got a cautious reception. But he persevered and eventually managed to make Ainu friends who invited him to visit.

A major challenge facing any photographer seeking to portray indigenous culture is how to avoid falling back on stereotypes.

For Isfendiyar, the answer was practical: wash dishes in a noodle bar.

Through multiple trips over a two-year period between 2016 and 2018, he immersed himself in the culture of a single Ainu community in Hokkaido Island and the family life of Kenji Matsuda.

His work in Matsudo’s restaurant drew curious reactions from tourists; the proprietor responded by identifying the photographer as his son – the ultimate mark of acceptance: “He ended up calling me his son and I’d call him Dad.”

Gradually the project took shape as Isfendiyar found his way into his subject matter: “A lot of the photos I had seen were in black and white or in sepia, and they had a nostalgic feel to them. I didn’t want to create that. I wanted to create something that was a bit more modern and gave the impression of something that is still alive, as opposed to something that of the past, of the bygone era.”

Many of the images in the exhibition were taken in a single four-day session on his last visit when it all seemed to come together in Isfendiyar’s head.

The photos are a mixture of highly choreographed shots depicting stylised visions of Ainu heritage – Matsuda in traditional dress holding a bow and arrow, Matsuda looking at a mountain in the distance; and vernacular photos of the restaurateur, his family and others in the community going about their daily business on the street, at work and at family events.

The two sides of contemporary Ainu culture are united in Isfendiyar’s photographs by a common colour scheme of dark blue and rust – the two dominant colours in Matsuda’s ceremonial garments.

Numerous Ainu make their living from selling such handmade traditional crafts – textiles and carved woodwork are specialities – and catering to the needs of visitors.

As with many indigenous groups, the Ainu have an ambiguous relationship with the tourist industry; it is a livelihood, but also a commodification of their heritage.

Can photography provide an alternative take on the Ainu to that scooped up by passing tourists?

Isfendiyar notes that the community he visited had formed around a pre-existing tourist trade that had drawn them in: “There is much more depth to the culture than you see initially if you just walk in for a couple of days and see the tourist industry. That is really just the surface of what they are producing to stay alive.”

But he also acknowledges that his photos offer only one of numerous possible interpretations of Ainu culture: “From going up there a few times, having been invited into people’s homes to see what goes on behind closed doors, you see that this is one perspective, because firstly it is through my eyes, and then it is through another man’s eyes.”

In a cultural group of 25,000, there are as many notions of ethnicity, and this fine collection of photographs is a salutary reminder of the diversity of all identity.

Master – An Ainu Story by Adam Isfendiyar is on until 10 April at Sway Gallery, 70-72 Old Street, EC1V 9AN.