Nutty by nature

Some of the things we call nuts can be more accurately described as pips, seeds or stones.

We use them as they are, in their outer covering or shell, or enjoy them shelled and pre-cooked or roasted.

We use their oil, or crush them into sauces or dips, preserve them in sweet or salty ways, and enjoy them as cheap ingredients, staple foods or luxury items.

Walnuts are available in Hackney, fresh in the summer, green walnuts in their outer skin, looking more like limes, and inside this, in their still not yet rock-hard shells, known in the trade as ‘wet walnuts’.

Later we can buy the ubiquitous California walnuts, in their shells or loose, dried to perfection to avoid rancidity, crunchy, but lacking the depth of flavour and texture of our own native nut.

And native it has been for centuries, the walnut probably originated in Persia and spread all over Europe, the botanical name Juglans regia, can be, but isn’t, translated as Jove’s balls, giving a classical gloss to a barbarian tree, nux gallica, with its aphrodisiac and healing properties, lovely wood, and a tasty kernel.

When Jove or Jupiter came to earth he lived only off walnuts, and so they acquired associations with prosperity, fecundity and rebirth.

Walnuts were tossed at the bridal couple during Roman weddings, and today sugared almonds are handed round in Italy and elsewhere.

Nocino, an Italian liqueur, was one of the many slightly bitter medicinal potions used by physicians in the past.

We smugly quaff these beguiling bitter drinks, amari, aperitivi, digestivi, Campari, Fernet Branca, Negroni and the ineffable Cynar made from artichokes, all intended to do us good, and hence feel guilt-free.

Nocino is made from green walnuts, steeped in alcohol, sugar and spices, traditionally harvested on 24 June, after the festivities of St John’s Night, with its pagan and christian goings-on, when witches and hopeful village maidens danced round the walnut tree dreaming of mayhem, matrimony, fecundity and the joys of summer.

In Italy, many families make their own, and a small glass (the smaller the better) at the end of a meal is said to help digestion.

The walnut comes in handy in many historic recipes, not as an ingredient but as a visual unit of measurement, accurate enough when all you need is an approximation, and immediately understandable where x grams of this, or fractions of an ounce of that, are too abstract for the busy cook.

‘Add a lump of butter the size of a walnut’ and you know what’s what, leaving the home economists to kick their digital kitchen scales to the bottom of the garden.

The Romans are said to have introduced walnuts to the British Isles, and one wonders how long it took to introduce the tree to occupied Wales, where military garrisons held disgruntled natives at bay.

Our sometimes footsore but always cheerful legionary once gave a mist of thought to settling in the Welsh Marches with his ample retirement pension.

It reminded him in some ways of the Italian Marches where his aunty in Macerata made a sumptuous layered pasta dish including wild mushrooms and truffles.

A smallholding sheltering in a grove of walnut trees at Llandewi Skirrid, on the way out of Abergavenny, was a tempting proposition. But the warmer climate and aunt’s cooking opportunity prevailed.

Some whiff of truffle oil from our friend’s kit must have lingered there for nearly two thousand years, to lure another genius from the Marche, Franco Taruschio, whose cooking at the Walnut Tree Inn was legendary.

Many of us who enjoyed this magical fusion of Italian gastronomy and Welsh ambience and ingredients look back on Franco’s Vincisgrassi with awe and gratitude. Our benchmark for Italian food in the British Isles.

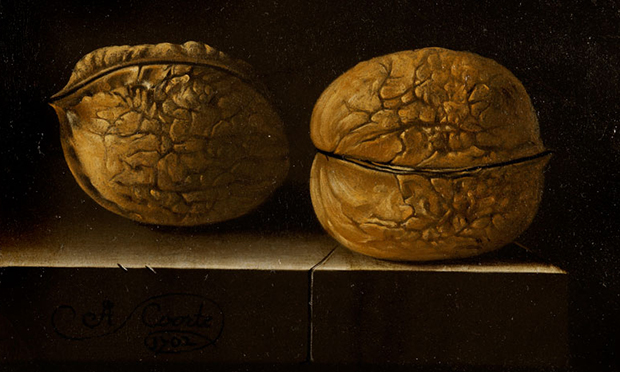

Walnuts can be seen in still life paintings, often alongside other nuts, and art historians have explained with great erudition their sometimes complicated symbolic meaning.

This ‘hunt the symbol’ is now known as the ‘iconological turn’ heaven help us.

But other historians hold that the ‘art of describing’, at a time when scientific method was being applied to painting, and the subjects painters and their clients enjoyed, this could bring clarity rather than obfuscation to our search for information.

So food historians can use what they see in still life and genre paintings, with caution, but a lot of pleasure, without getting all confused and worried about how to understand what we hopefully see as just ingredients, but might have a heavier load of meaning.

Many objects in a still life can be construed in various ways, the walnut’s hard shell can signify the wood of the cross, and the nourishing inner kernel Christ’s redeeming love for mankind.

A loaf and a glass of wine, can refer to the bread and wine of the sacrament, or a blemished apple is a sign of inner corruption.

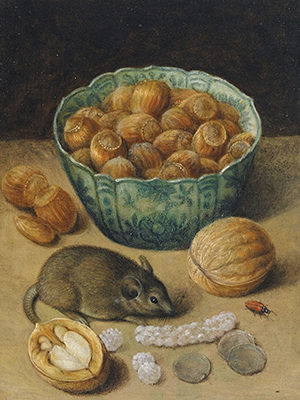

The small painting by Georg Flegel, of a little mouse enjoying a domestic meal, is loaded with symbolism, but is also an accurate view of a typical snack in 17th century Low Countries, and the hazards of housekeeping.

Another painting by the same artist deploys the bread and wine theme with a dramatic sight of a pretzel dunked in a glass of wine, along with some walnuts.