‘The Empire was a commonwealth of recipes…Britain was fortunate in having access to many of them’

Detail from Adriaen Coorte’s Strawberries Mauritshuis (1696). Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

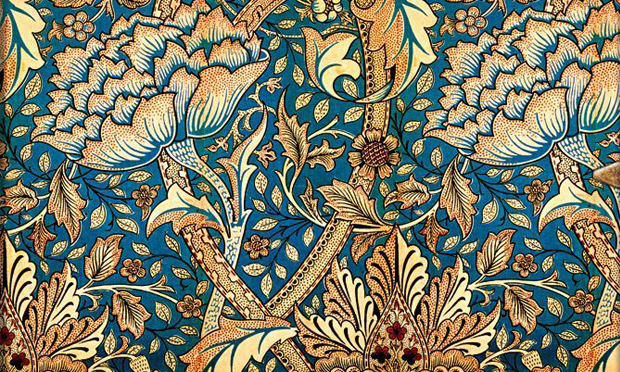

When William Morris registered his gently flowing floral wallpaper and fabric pattern in 1883, he gave it the name Windrush, after the gently flowing tributary of the Thames that wound through the sleepy Cotswold villages around Boughton on the Water, not far from Kelmscott Manor, where he could escape the pressures and worries of London life.

The decorative floral design seemed part of the ‘Englishness’ of the landscape, and the charm of the pretty stone cottages and manor houses recalled a time when decent people could earn a decent living doing work that was both useful and enjoyable.

That is what fired Morris’s Socialism, the right for everyone to a life of honourable employment, doing well-paid and worth-while work. He was aware of the contradictions – the comfortably-off clients who could afford to buy his hand-printed fabrics had to be converted to the idealistic politics of ‘One for all, and all for one’. An idealism tempered in the gritty in-fighting of the various socialist factions in London of the 188os. This is the introduction to a speech Morris made in 1894:

How I Became a Socialist

I am asked by the Editor to give some sort of a history of the above conversion, and I feel that it may be of some use to do so, if my readers will look upon me as a type of a certain group of people, but not so easy to do clearly, briefly and truly. Let me, however, try. But first, I will say what I mean by being a Socialist, since I am told that the word no longer expresses definitely and with certainty what it did ten years ago.

Well, what I mean by Socialism is a condition of society in which there should be neither rich nor poor, neither master nor master’s man, neither idle nor overworked, neither brain-sick brain workers, nor heart-sick hand workers, in a word, in which all men would be living in equality of condition, and would manage their affairs unwastefully, and with the full consciousness that harm to one would mean harm to all—the realization at last of the meaning of the word COMMONWEALTH.

Morris would have been the first to relish the irony of naming a captured German warship, the Alma Rosa, Empire Windrush HMT.

William Morris’ Windrush pattern. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

She began life as a low-cost cruise ship, then was used during the war to transport Nazi troops (and carry some Norwegian Jews on their journey towards Auschwitz). Captured in 1945, renamed in 1947, and used as a transport ship, the Windrush we cherish today already carried quite a load of not altogether comfortable associations.

But for the British citizens arriving in 1948 from the Caribbean it seemed to offer an honest and honourable future. Today the food stores, bars and market stalls of Hackney give some idea of the success of that venture, and our intrepid restaurant reviewers have told of the many gastronomic delights we can enjoy thanks to Windrush.

A commonwealth of ingredients

Our usually hyperactive legionary was seen bathing his sore feet in a gently flowing stream, on his way to spend a few days leave with nouveau riche friends in their villa at Chedworth in the Cotswolds, with its vulgar mixture of mosaics and murals (Terence Conran meets Laura Ashley), but redeemed by delightful underfloor central heating and what we would now call a Turkish bath. The food not bad, with local strawberries and a delicious a custard of raw asparagus and eggs, seasoned with fish sauce and black pepper.

He mused on how Roman Britain was the only place, in many years of military service all over the Empire, where his skin colour had been an issue; the smug Romano-British Cotswold settlers suggesting he might wish to go back where he came from…

Well yes, those lovely Ligurian pancakes, the Egyptian foul in pitta bread with dukka, the quince and honey preserves of Byzantium, and the amazing things the Picts do with sheeps’ innards and some of our expensive black pepper, and the weird ways with fish that the wicked blond warriors from Nordic lands brought with them..

The Empire was indeed a commonwealth of recipes, a mosaic of ingredients. Britain was fortunate in having access to many of them.

Biff-worthy

I sometimes want to biff the smug cookery writers who insist that the only way to enjoy the evanescent flavour of fresh asparagus is to rush the spears from the kitchen garden to the pot of water boiling away on your pale blue aga. You wot mate?

A recipe from the ineffable Sally Grainger (Cooking Apicius, p.51) shows how Apicius handled things: Raw asparagus spears are ground to a pulp in a food processor, strained to get all the liquid, which is mixed with eggs and seasoned with fish sauce, olive oil and black pepper. Then cooked in a very low oven in a dish placed in another shallow dish of hot water, until the savoury custard is set.

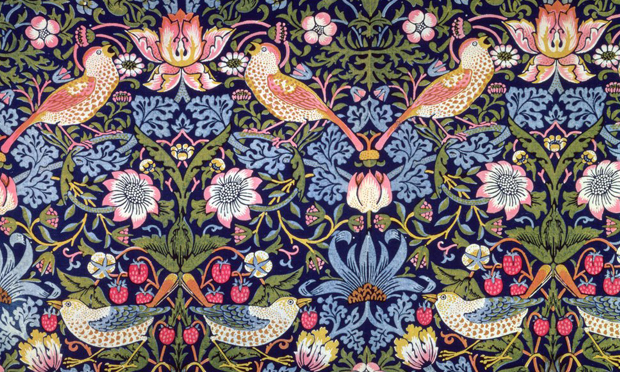

William Morris’ Strawberry Thief. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Another William Morris fabric, Strawberry Thief, depicts fat thrushes greedily pecking away at the strawberries in his kitchen garden at Kelmscott, a kindly view of a predatory situation.

Which leads to a further biff-worthy observation – that sun-kissed strawberries ripened on the plant and eaten on the spot are best of all. Well yes, those thrushes got it right. But the rest of us have to make do with fruit picked early to avoid spoilage, delivered in hygienic air-conditioned transport, and sold from a chilled display cabinet, with a pretty good chance of the fruit going mouldy before ever managing to ripen. Some green grocers manage to get it right, and it’s worth paying for.

Until the end of the 18th century strawberries, cultivated and wild, were the small fruit of fragaria vesca, now replaced by the bigger garden strawberry, which can be grown more successfully. Adriaen Coorte’s many still lifes of strawberries and asparagus give some idea of how much they were enjoyed in the past.

But if faced with less than fragrant bloated specimens, one can make a nice salad: using sliced cucumber, sliced strawberries, chopped chives and mint, seasoned with salt and freshly ground black pepper, olive oil and a few drops of lemon juice. Crushed strawberries, tempered with a little salt and sugar and just a few drops of best quality balsamic vinegar make a nice fresh sauce for rich roasts and barbecues.

What a relief to come clattering down Stamford Hill, back to familiar old Londinium, with the air vibrant with aromas of slow-cooked pastrami, the pungent whiff of ackee and salt cod, the crunch of stamp and go, and the ever-present whiffs of freshly baked bread and the comforting warmth of Appleton rum. Home at last.