I Drilled A Hole in My Head to Stay High Forever: counterculture icon fails to bore at MOTH Club

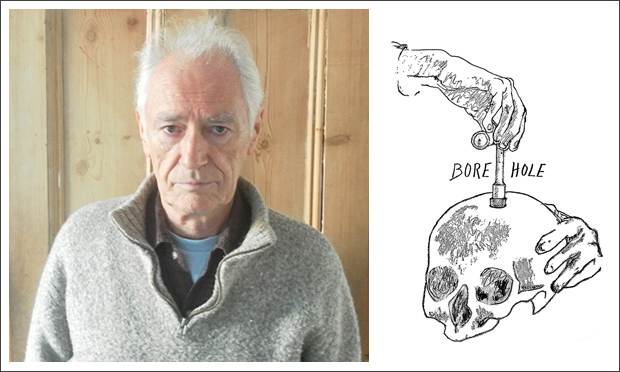

Hole-y Man: Joey Mellen and the cover of his psychedelic memoir, Bore Hole. Image: Joey Mellon / Strange Attractor

Joey Mellen’s Bore Hole memoir has captivated successive generations of seekers of alternative culture.

Its appeal is probably best summed up by the simple poetry of its first paragraph, which promises within the story of how the psychonaut and consciousness explorer (now in his late 70s) came to one day drill a hole in his own head in order ‘to get permanently high’.

Mellen’s self-trepanation (the drilling of said small hole into his skull), and the film that he and his ex-partner Amanda Feildling made of hers, Heartbeat in the Brain (1970), has secured for him a countercultural cache that still entrances those interested in the furthest reaches of human experience. And it was a cache that Mellen’s rare live appearance at the MOTH Club, organised by Hackney screening club Deeper Into Movies, was keen to tap into, attracting a varied audience of the initiated and curious.

Interestingly though, Mellen delivered a talk that was far from the outlandish tale of debauched psychedelia that it seemed many of the audience (and perhaps the organisers themselves) might have been expecting.

Valette Street venue MOTH Club was the scene of Mellen’s talk. Photograph: Paul Hudson via Flickr

Rather than spending much time talking about the procedure, Mellen outlined in a surprisingly medical level of detail his theories of trepanation and its associated health benefits.

Reflecting on his own introduction to these concepts by his mentor Bart Hughes, he talked at length about how blood moves around the body, supplies the brain and is affected when high.

At times struggling with the low light and some technical difficulties whilst reading from his copious notes, he explained how he and other advocates of the procedure believe that the blood constriction caused by the fusing of the skull, something that happens between 18 and 22, causes a reduction in brain power.

More blood in the brain equals heightened perception, accounting for the extraordinary responses of the brain when high. Trepanation frees the brain from a solid bone prison, allowing it to pulse like that of a child and increase circulation.

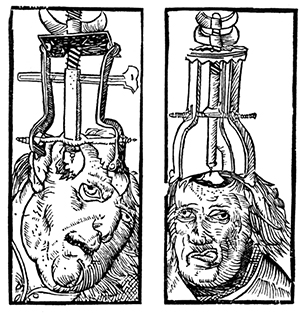

Trepanning is an ancient process, as this 16th century engraving illustrates. Image: Wikimedia Commons

For Mellen, trepanation is an escape from adulthood, a state he suggests as the ‘ultimate coming-down’.

Mellen pursued this academic approach to the altered states he has experienced throughout, defining them not by the fun he had but by the potential of the brain realised.

A surprising but revealing example amongst all this was that hallucination was never, for him, the point of his experiments with LSD, prompting some tips for the crowd on avoiding the glucose-lack that might ruin a trip with unwanted visions.

For Mellen and devoted consciousness expanders, being high is a serious business, and it was clear at points that this somewhat dry presentation of research findings was perhaps a little unsuited to a hot Sunday MOTH Club.

At times, Mellen’s talk was a timely reminder that most of the great 60s pioneers of mind expansion, from Timothy Leary to RD Laing, were slightly paternalistic older gurus, feeding hungry seekers of a different experience with loosely linked elements drawn from science, religion and philosophy that require close attention and devoted study.

Bore Hole is fascinating text that will endure. As long as there are those determined to seek out the furthest limits of their mind, it will find an audience and entrance those who read it.

This particular talk though was oddly positioned as a head trip event by the organisers, from the psych-DJ and projection for the hour before to the marketing blurb that attracted its audience.

It would have been better put forward as a literary talk or research event, advertised as a space for sustained consideration rather than counterculture adoration.

Despite the opportunity to see a legendary figure in the flesh, Mellen’s book still remains the best way to access his fascinating story.