Woodberry Down artist ‘comes clean’ as visually impaired as he celebrates 90th birthday with exhibition

“If that old bat can do it, so can I!” Peter Gosnell in front of two of his pastel works. Photographs: Andrew Barnes

Peter Gosnell, resident of Woodberry Down since 1955, is a master of pastels and marker pens, with a knack for light and composition that has seen his work exhibited in places like Pall Mall and the Banqueting House, and toured around the country by The Pastel Society.

He’s also been registered blind for almost 70 years.

“My principal problem is retinitis pigmentosa (RP). I went to a specialist when I was 16, and he told my mum I’d probably be blind by time I was 21.”

When I met with Mr. Gosnell (alongside his wife June and proud daughter Elaine) at his home at the very tip of the Hackney side of Finsbury Park, he summed up his determined reaction to this news as: “ah, go to hell. I didn’t take any notice.”

Sure enough, a week later, he decided to start violin lessons, before a pivot to visual art – art that will be celebrated with an exhibition at Redmond Community Centre (by Woodberry Wetlands) starting from Monday evening, 21 August, a week after his 90th birthday.

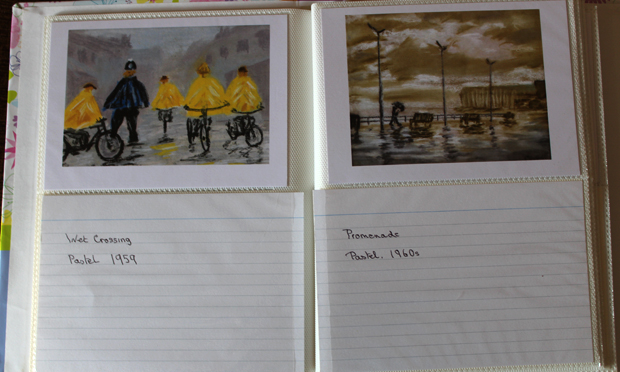

Prints of Wet Crossing and Promenade by Peter Gosnell

Gosnell’s education progressed despite a knock-back from a Chelsea school because of his deteriorating eyesight. He received more tailored tutoring at the now-defunct Ensham School in Tooting until the summer of 1939, and Chamberlain’s fateful broadcast from the Cabinet Room.

Having been evacuated to Chichester during World War II (with the Battle of Britain being fought practically right over his head) young Peter dreamed of coming home, all the while sketching the hours away – dogs were a popular subject, but other than that, London played on his mind.

“I didn’t draw Chichester the whole time I was there,” he jokes, and the evidence hangs on his wall, in the shape of a pencilled Piccadilly Circus from 1941. Another drawing of St. Paul’s was subtitled Homesick Evacuee.

The original of Piccadilly Circus (right) hangs on Gosnell’s Woodberry Down flat

Chichester took Gosnell’s art to its heart though, with then-Mayor Stride joining the chorus of praise in the Chichester Observer when he auctioned some works off for War Weapons Week and the like.

At the civil service, where he found a 31-year career upon his return to London (after a stint in a busy Greek Cypriot hairdressers’) the ambition to take his hobby further was triggered in him.

They had “clubs for all sorts” at the time, and he remembers receiving a circular about the Art Club and visiting their annual exhibition in the Ministers’ conference room:

“I was looking at one picture, looked down the list in the catalogue, and it was by a women in the office I worked in. And y’know, she seemed old to me at the time (she was in her fifties) and she wasn’t anybody’s best friend…

“I looked at this picture and I thought ‘If that old bat can do it, so can I!’”

But what medium to pursue? “Oil was out. We had two young daughters – where can I put an easel with an oil painting drying in a two-bedroom flat with two little girls running about?”

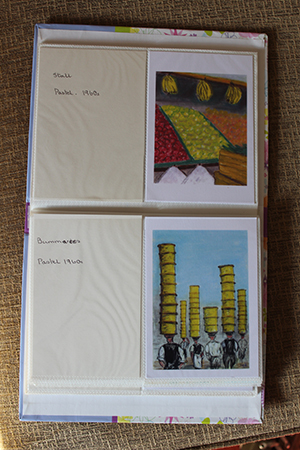

Eventually, a mop-topped, bow-tied colleague suggested artist’s pastels as perfect for Gosnell’s style and lack of a fancy studio, and he began turning out more of his pastel or ink studies in light, patterns, shapes and visual gesturing.

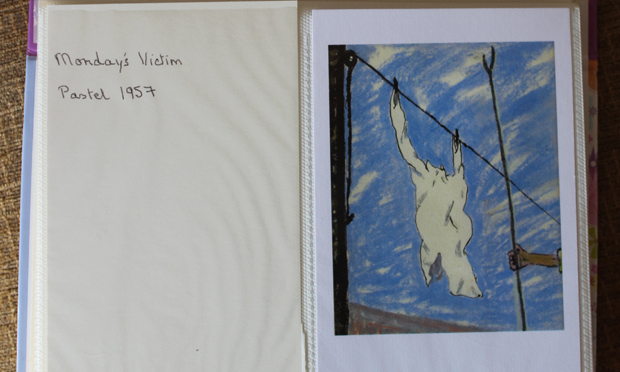

As his work drew more and more attention and notices (his Monday’s Victim was included in the national civil service exhibition at the Guildhall, and two more pieces found their way into The Pastel Society’s prestigious annual showcase) Gosnell quietly carried out his intention to not mention his RP to anyone in the art world, to let his creations stand on their own.

He explains: “With retinitis pigmentosa, I could be very deceiving to other people. Because I could be out, read a book, read a newspaper. For years! Registered blind. Out in the street at lunchtime, I could run, weaving in between people, jump on a bus at the traffic lights, and people would think “I thought he was registered blind?”

“But I could get off the bus, walk into a shop, bump into someone and fall downstairs!” – citing the condition’s early-stage symptom of visual gloominess and maladjustment to light.

Gosnell talks at length of taking in works from Degas to Picasso despite his lack of sight. What interests him in these images, like in his own, is the rules of composition – the nuts and bolts of why his and others’ images work in the mind’s eye.

Speaking about his own Wet Crossing: “It’s four cyclists with yellow capes, and a policeman. Now who on Earth wants a picture of [that]? Who the devil wants to hang that on their wall? But you look at it, and there’s something satisfying about it… It’s simply an arrangement of triangles.”

Life took precedence over art after the seventies, and soon Peter’s granddaughter Lydia inherited a different kind of artistic talent – she plays in recorder quartet Palisander.

However opportunities to use his unique talents do crop up – his Piccadilly Circus featured in the Imperial War Museum for a time alongside an audio loop of his evacuation memories, and an image of a plasticine goalkeeper he made formed part of a photo-collage mural, celebrating his beloved Arsenal’s move from Highbury to the Emirates. Originally running the length of Arsenal tube station, this can be found, by entrance 7, inside the colossal stadium to this day.

Which indeed brings us back to the present day, and the coming celebration at Redmond Community Centre. And the big revelation of his registered blindness? He says it doesn’t matter to him anymore, but explains his rationale:

“I had always wanted to do things, and I spent my whole working life alongside fully-sighted people doing the same work as them… All those years ago, the last thing on Earth I wanted was for people to know that the ‘person who painted that’ was registered blind. I didn’t want sympathy – just [to know] ‘how good is it?’

“I’d just want to know, what are its good points, and what are its bad points – so I can correct them next time. If I was still painting, I wouldn’t want it known now!”

Peter Gosnell’s exhibition Fancy That is at Redmond Community Centre, Kayani Avenue, N4 2HF, from Monday 21 August at 6pm, and is planned to run until the end of the month