Homerton Hospital’s surprising commitment to art continues – with a little bit of politics

Chromik ‘art condition: Shaun Caton stands proudly in front of Underbelly Britain. Photograph: Andrew Barnes

Homerton University Hospital is many things to many people. It could be the site of one’s first breath and their eventual demise, hosting all the fun ailments and leakages that come along the way.

But I’m not here to leak or die, I have an appointment with the hospital’s Art Curator and Programme Manager, Shaun Caton, to see something familiar in this most unfamiliar location – an exhibition.

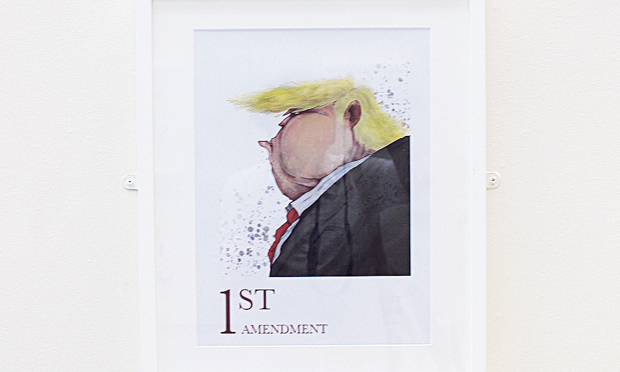

Not just any exhibition, a highly political one: Underbelly Britain showcases Stewart Chromik’s satirical illustrations, which broadly fall midway between James Gillray’s more formal political caricature, and the grotesquery on show in the work of The Guardian’s Steve Bell, Viz and even certain Beano strips.

1st Amendment Trump by Stewart Chromik

I asked Caton how he came across the London artist: “Totally by chance. He just phoned up and said “do you want a mural for your hospital?” and I asked “what of?” Then he sent these pictures, and I thought “there’s no way we can put this in a mural, it’s too radical!” But then I thought about it – maybe not a mural, but an exhibition.”

Contrary to the febrile national mood (but maybe unsurprising in Hackney), Caton tells me that no-one so far has been offended by Underbelly Britain.

“People were very responsive to this, because it’s topical, and the themes are still occurring in our society. There’s been no negativity, no flack – in fact I’m very surprised at the solidarity.

Stewart Chromik’s Three Lions

“People support it, enjoy it, and see it for what it is – humour. Which unfortunately our society has seemed to have lost, temporarily.” He points me towards a ribald drawing of what appears to be homeless alcoholics, viewable above.

“This is perhaps somewhat radical in a hospital, where people are suffering from illnesses related to these kind of things. But we have to address it… By using humour in a time of adversity and upheaval, it softens the edges a bit, it can inject a laugh rather than fear.”

Underbelly Britain is the 54th of Homerton’s rolling program of exhibitions. They run four a year, have private views, and sell many of the pieces too, similar to a more traditional gallery set-up. One recent example, Roots to Reckoning, looked primarily at African-Caribbean culture. Another hosted Preposterous Postcards.

But little did I know that this is just the surface level of Homerton’s commitment to art. There are thousands of artworks in the hospital’s collection and dotted around the various medical units, all amassed over the last 30 years (galleries like White Cube have also donated to top up the supply).

Knowledge of this fact got Caton his job in the first place. “There wasn’t a job when I started, [the role] didn’t exist. There was a huge collection of art, and I wrote to the hospital authorities and said “do you realise this is worth a lot of money? Does anyone look after it?” And they said, “well do you want to?””

Some nuggets from the Homerton Hospital collection

It’s a role he takes seriously, as an artist (and contemporary of Damien Hirst) himself – trawling eBay for bargains, ordering special light damage-proof glass, and building relationships with museums like Museum of Childhood (a photo-exhibition of their undisplayed toys was particularly popular with children).

Caton is a man in demand within the hospital – we are stopped on our stroll by a senior nurse looking to revamp her department (they all share a desire to “make their department look special”, he explains.)

Perhaps the most quietly amazing part of Homerton Hospital’s artistic provision is actually located in a clinical area. The Regional Neurological Rehabilitation Unit houses people with “profound disability… brain injuries, dementia, people that are recovering from strokes”.

Therapeutic: a view of Homerton’s art room

Twice a week, patients decamp from the main wards to a studio room that would be more at home in some kind of arty warehouse, and take part in art therapy workshops that are run, not by clinicians, but by actual artists: from filmmakers and graphic designers – even sound artists – to more traditional painters and printmakers.

There’s more information on this dazzling room and the groundbreaking therapy done there in a 2015 piece in our former sister paper, East End Review. Since that article, hospitals in Japan, Canada and the USA have visited to take inspiration from the Homerton’s therapeutic model.

Next time you visit Homerton Hospital (and unless you want to, I hope it isn’t soon), look out for some of Mr. Caton’s pet paintings and prints lining the walls – they’ll inject some soul and cheer into your stay.

Underbelly Britain runs until 27 August