Where have all the Grannies gone? Gillian Riley on Latin American food

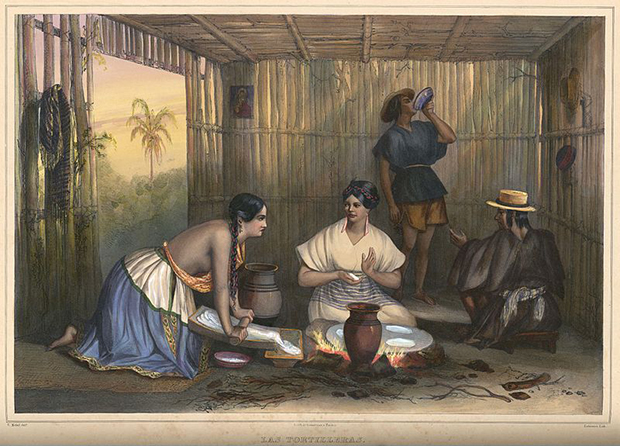

Las Tortilleras, one of the 50 plates in Carl Nebel’s Voyage pittoresque et archéologique dans la partie la plus intéressante du Mexique

Here in Hackney we take for granted the high quality of Turkish restaurants and food stores. They are just part of the air we breathe. And they owe everything to the flourishing home cooking in every Turkish kitchen in the borough – the cooking of the Grannies.

We sometimes glimpse them in the front windows of bakeries, well wrapped up in apron and headscarf, sitting comfortably on low stools, rolling out lumps of soft bread dough, carefully spreading a filling over one half, then folding it over and flipping it onto a hot convex metal dome, where it cooks in minutes, during which time Granny has rolled out another gözleme, ready to cook. No fuss, no flapping, none of the theatrical posturing of the pizzaiolo.

Turkish food eaten out has to come up to home standards, simple, honest, unspectacular but tasty, and we look for similar cuisines in vain in the trendy ‘ethnic’ offerings in some smart corners of Hackney. That’s why the search for Latin American food can be strangely unrewarding.

The vibrant music, bright lights and miasma of cocktails can dull our responses to the food on offer; a calculated assault on both authenticity and edibility. Some of these joints don’t deserve the oxygen of publicity by naming them, so only a passing reference here to an allegedly Mexican place nobbut a step from where I sit, where the punters, smashed by hallucinogenic cocktails, can no longer register the sheer awfulness of the bought-in food on offer. No grannies, no home cooking, much grief. We’ll come back to happier takes on Mexico later.

Meanwhile a look at the potential scope of Latin American food, so many countries and cuisines, listed here according to size and population: Brazil , Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Peru, Venezuela, Cuba, Ecuador, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Uruguay, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Haiti, a huge continent with massive variations in climate and terrain, a vast range of products, seasonings and cooking techniques, and influences from all over the world.

It would take a welcome surge of mass immigration to fill Hackney with the clients and ingredients and grannies to offer just a few of these cuisines.

The demographics of the borough can’t operate with the same dynamic as the Turkish community, we’ll never get the bedrock of citizens, with all the fixed certainties of long residence and employment, traditional cooking and accessible ingredients.

What we do enjoy from Latin America are the glamour and excitement of its bars and street food, recreated with manic inventiveness by brilliant young chefs unhampered by tradition and the lack of ethnic ingredients.

Many of these ingredients can in fact be got in food stores and markets, from tropical fruit and veg to the spices and fresh chillies and coconut and dende oil and the various weird and wonderful cuts of meat, fresh and cured, that it would be foolish to disdain.

The Brazilian store at the top of Stamford Hill is unspectacular in appearance, but has all you need for a fine feijoada, one of Brazil’s finest dishes.

‘Heaving peasant hotpot’: a bowl of feijoada. Photograph: Helder Ribeiro via Flickr

Its meat section is awesome, with all the nose to tail bits and pieces you need to make this satisfying dish along with the renowned Brazilian sausage linguiça, a highly spiced smoked pork sausage, rather like the lucanica sausage, that the Roman soldiers are said to have enjoyed when on duty in Lucania, a pig-rearing district in the province of Basilicata in the south of Italy, and maybe brought by their legionaries to the north, which also claims it as a speciality.

Some writers claim that the Romans ‘invented’ feijoada, or they nicked it from the Portuguese, or took it with them to Portugal, and spread it round the empire, so we can almost imagine the homesick, tear-stained legionary, tottering up Stamford Hill with his heavy pack, stopping off for a bag of black beans and some farofa at the Brazilian Centre to lug along to base camp, where surely bits of salted and smoked pig and weirdly interesting meats would be waiting to be added to the pot.

Some years ago an idiosyncratic café called Tierra Brasil used to be the second home of users of the British Library, where the owner would revive us with home-made moqueca, a fragrant fish soup with coconut milk, garlic and fruity peppers and chillies contrasting with fish and prawns marinated in lime juice. Her feijoada was so pungent and overpowering that it was kept for Sundays when the library was closed, and readers could safely indulge in the house caipirinha, eat their fill, and sleep all the way home on the 73 bus.

Everywhere throughout history there have been tasty dishes, like feijoada, of pulses or beans soaked and then simmered with obdurate lumps of fresh and cured meat to produce a fragrant stew, to which can be added local herbs, vegetables and sometimes sharp fruit. Cassoulet in France, the Tuscan Fagioli all’Uccelletto (vegetarian, but sometimes with sausages), or the Cassoeula of Milan (mainly pig parts and cabbage), the Cocido Madrileño (various meats and garbanzos, chickpeas), are just a few.

Of course there is no way the Romans could have known the black beans of Mexico, and the cassava of Africa, the tomato, chilli, vanilla, cocoa, and all the good things that came to Europe from the New World after 1492, but they would have stewed cured meats and things like ears, snouts, feet and jaws, and organs and extremities with lentils or dried broad beans.

We can recreate these various heaving peasant hotpots at home, without risking the disappointments of eating out.

Gillian Riley gets to grips with a Mexican tortilla press. Photograph: Annalies Winny

That’s what we did some years ago, when I wanted to find authentic Mexican food in Hackney and ended up in my kitchen with a team from Hackney Citizen toiling away with comal and tortilla press, and toasting, soaking and mashing the wonderfully fragrant chillies ancho, pasilla, mulato, and a load of other things to make our version of mole poblano, perhaps the first ever fusion recipe, combining ingredients from native America with those brought by the Spanish conquistadores.

Things have improved since then, Santo Remedio gave us some fine Mexican food, Club Mexicana at Pamela is vibrantly vegan, and the bold spirits behind Breddos, who make no claim whatsoever to authenticity, are inspired by Mexican street food to conjure up sparklingly audacious combinations of flavour and texture on the solid bedrock of tortillas, tacos and tostadas made with their own fair hands on the premises using masa harina specially prepared in house. And not a granny in sight.

Masa harina is a maize flour that has been ground from maize treated with alkali (lime or ashes) to soften and discard the tough outer skin of the kernels. The chemical effect of this, a process known as nixtamalisation, does wondrous things to the nutritional properties of the masa, creating niacin, amino acids and extra protein and vitamins. So Mexican peasants in the past had a cheap, healthy and balanced diet eating these tortillas with beans, chillies and tomatoes, with little if any meat. They survived and flourished. But when maize got to Europe, and was cultivated all over northern Italy, and prepared without the nixtamalisation, its paucity of nutrients caused deficiency diseases like pellagra on a huge scale, with resultant social and economic misery. No fear of that in Hackney.

If our dear, good mayor Philip Glanville ever got Trumpish thoughts about walls and Mexicans he might dream of building a small but perfectly formed one in Clerkenwell, to keep Breddos and all its glories safe for us Hackney Citizens until the last crack of doom. This being, as some foodies claim, the Year of the Taco, we need all the help we can get.