Novelist Alan Gibbons on why he is opposed to forced academisation and ‘exam factories’

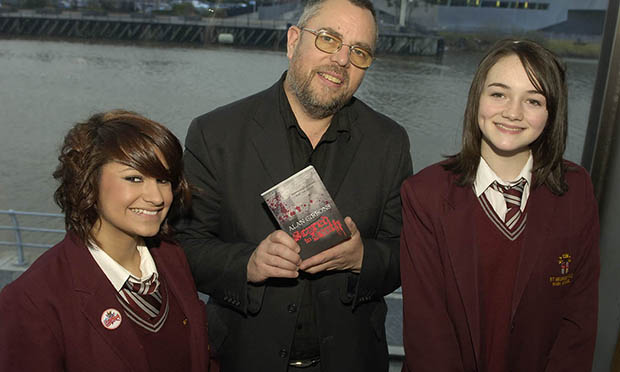

Alan Gibbons with pupils and one of his youth novels

Alan Gibbons, a former teacher turned children’s fiction writer and education consultant, spoke earlier this year at a packed meeting of Hackney parents opposed to forced academisation. Since then Hackney Council has proposed setting up a multi-academy trust, which could potentially mean every school in the borough being turned into an academy.

We caught up with Gibbons and asked why he got involved in the campaign.

Why are you against forced academisation?

Without any evidence of any improvement in standards, the government seems determined to go ahead with academies. There’s quite a lot of evidence that says local state schools do at least as well and probably better than academies.

To most local parents, academisation is a move away from democratic control of schools. In the present set of government guidelines, that means, for example, that parent governors might not have the same rights – there would not be the same parental input.

What that boils down to is that instead of local authorities having democratic control of schools in a way that the electorate can enforce some kind of scrutiny and transparency, all power actually devolves into two sets of people. One is the Secretary of State for Education, and that’s ironic when this government continually says it’s about local accountability and localism, and the second are executives of multi-academy trusts. That’s highly problematic.

But hasn’t the government dropped these plans?

I described it not as a U-turn but as a new-turn – you know, like the wildebeest that weaves and tries to get away from the lion. They dropped the idea of comprehensive forced academisaton. It was hugely unpopular and it was bringing all the teaching unions together. What they’ve gone for now is to essentially say that when schools have issues then academisation goes through – and they make it incredibly difficult for local schools to carry on as state schools.

So instead of taking on all schools together, they are taking a kind of back route approach to cherrypick and nibble away at school after school, but ultimately with the same aim of getting all schools to be academies.

You also campaign against current testing levels in schools. Why?

Children are permanently in a state of tension over tests. Across Europe, schools that are doing better than British schools in comparative testing and data very often don’t even start formal education until ages six or seven. There are far fewer high stakes tests in most of those countries.

When we look at countries that have high levels of testing all the time, for example South Korea, suicide rates among teenagers are higher. Some Far Eastern students will do five-and-a-half hours in schools and then they’ll do a similar number of hours in cramming tests.

What I want is monitored, formative testing. That means that we trust the judgment of teachers. Our government has said this is about testing the teachers, not testing the children. Well, if you want to keep an eye on schools, then sampling – taking a sample of schools and testing those to check that the whole education system is working well – is a much less onerous way of doing that.

What led you to get involved in campaigning on these issues, and is there a growing appetite among parents for pressuring the government to change tack?

I’ve seen the impact of over-prescriptive testing all over the world. I also saw lots of education systems that were doing really well and which didn’t have this obsession with testing and league tables.

There has to be testing and accountability, but it can be done a lot more easily and with less pressure on children. That is a message that was received by the parents in East London very well. They wanted their children to have a childhood. They wanted them to do well at school but they wanted them to have a childhood. That’s the central issue – the quality of children’s lives.