Hackney Propaganda: a look at 19th century working men’s clubs

You don’t have to look far to find examples of how East London is changing, either on the streets or indeed on this very website. Continuity – our closeness to the past – is unlikely to make headline news, though to the social historian it is of equal importance.

Author Ken Worpole acknowledges the difficulty of simultaneously holding a sense of change from and proximity to the past in his excellent introduction to Hackney Propaganda: Working Class Club Life and Politics in Hackney 1870–1900.

The pamphlet, which Worpole co-authored with the lecturer and historian Barry Burke, was first printed in 1980 by Centerprise, a radical community centre on Kingsland Road sadly now defunct, and is an extended version of two talks given there in the autumn of 1979.

“The contradictoriness of the past is captured in the popular expression, ‘the good old bad old days’, in which, of course, we continue to live”, writes Worpole in his introduction, and what follows is a brief survey (40 pages) covering Hackney’s working men’s club movement and socialist organisations during the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Radical intellectuals such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Daniel Defoe and Isaac Watts are given their due in Hackney with proposed statues and streets and pubs named after them. But for working class people in Victorian Hackney, free thought and political independence were impossible without a formal education and better living conditions.

After the Reform Act was passed to extend adult suffrage in 1867 and the founding in 1864 of the International Working Men’s Association came a boom of groups and organisations representing unorthodox ideas and non-conformist thought.

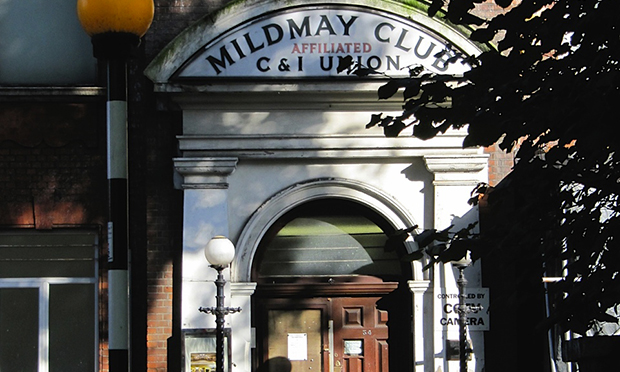

The working men’s club was a hotbed of oppositional opinion. An alternative to the public house, it was a heated and well-lit environment where men could drink ale, enjoy entertainment and educate themselves.

The Borough of Hackney Club, which opened in 1873, contained a reading room and a small library, and its activities included “weekly discussions and lectures on political and social questions”.

By the 1880s, according to Charles Booth’s survey Life and Labour of the People in London, there were 115 clubs in Hackney and East London. “To many more club life is an education,” Booth wrote.

The authors look at the members and activities of several clubs of the period, clubs with names such as the Homerton Club, the United Radical Club and the

Kingsland Progressive.

Some of the clubs were explicitly socialist, distributing literature in the streets and holding meetings that were broken up by police. Others provided an audience and venue for speakers such as William Morris.

Walking through Hackney, it is difficult to gain a sense of what the borough used to look like 130 years ago, let alone feel any connection to the people who lived in those times.

But Warpole and Burke provide anecdotes and vignettes about those long forgotten people who once inhabited Hackney’s streets, which entice the reader and force us to engage imaginatively. They also draw neat conclusions about the legacy of those times on the politics of today – though the today referred to is 1980. To make Hackney Propaganda relevant to 2015 would require at least another chapter.

Hackney Propaganda: Working Class Club Life and Politics in Hackney 1870–1900 is available from Hackney bookshops and at worpole.net. RRP: £5.