What is the future for Harringay's warehouse district?

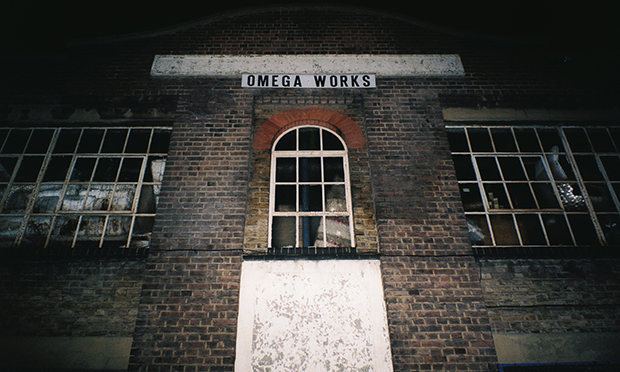

The front of one of the Omega Works warehouses on Hermitage Road, Harringay. Photograph: Ossi Piispanen

“Artists and African churches always move in at the same time,” says Ellis Gardiner, as he describes how he arrived in what is known variously as the Manor House or Harringay Warehouse district in 2000 with plans to set up a recording studio.

Fifteen years on, we are sitting in the ground floor of an old Courtney Pope building on Eade Road – part of a sprawling industrial site consisting of around 322 units across 42 sites. Once the area’s major employers in the shop fitting business, Gardiner and others have transformed the building into the New River Studios, comprising a recording studio, affordable office space and a café. Rising above the other side of Seven Sisters Road is a glinting totem of plate glass that is Hackney Council’s flagship development Woodberry Down.

The cross-subsidising model of Berkeley Homes’ mammoth project – where luxury penthouse flats are sold to fund the building of new council homes – is an increasingly popular one among cash-strapped councils.

Walking around the warehouse cluster the Berkeley tower pokes up above every chimney turret and single storey factory, a constant reminder of top-down regeneration and the steady spread of capital inching up from Shoreditch via Dalston and Stoke Newington.

Shulem Askler began buying up property on Eade Road in the nineties, when the ‘rag trade’ fell into decline and Harringay’s smaller textile factories accommodating Greek and Turkish dressmakers, sewers, packers and button makers began to close. His company Provewell Ltd now manages around 70 per cent of the warehouses in the area on behalf of its owners (mainly offshore investors).

Beginning with blank slates (“They had no bedrooms or doors,” laughs Askler) these industrious new tenants designed their own homes and workplaces. Other than a few rogue ‘architectural nightmares’, many are spaces that could grace the pages of interior design magazines; vast communal spaces decorated with projector screens, pool tables and wild plants, daring staircases and the obligatory space-saving mezzanines.

Gardiner – something of a warehouse everyman – is also a leaseholder on a former Fed-Ex warehouse appropriately named Ex-Fed, home to around 25 people. “It’s like a vacuum, creative people just flood in,” says Gardiner.

Now more than 1000 people live here. Hundreds of self-employed artists, makers, musicians and entrepreneurs have set up shop inside the live/work units. An internal Facebook group, fiercely guarded by its administrators, is a good place to view the micro-economy in action. Services and jobs are advertised, alongside parties and odds and ends for sale. Organisations like Haringey Arts work to connect artists with each other and provide a legal framework for those looking to apply for arts funding, while events such as May’s InHouse Festival offer a jam-packed programme of film, music, theatre and art held over six warehouses venues.

Unauthorised living

All this was bubbling away nicely until a Haringey Council officer visited one of the units on Hermitage Road in summer 2013 following a fire and was shocked to discover bedroom after illegal bedroom tucked away in an industrial unit. Despite the fact tenants had been paying council tax for over 10 years, the authorities were apparently unaware of the scale of the residential use. Initially Haringey Council went in guns blazing and requested £660,000 to tackle “unauthorised living in industrial areas”. One councillor described the warehouses as “cramped, cold, unsanitary and dangerous”.

Opposition to the evictions was quickly mounted by Warehouses of Harringay Association of Tenants (W.H.A.T.), and after an enforcement notice seeking to reverse the unauthorised residential use in Ex-Fed was quashed in a legal case, the council was pressured into performing a tentative yet significant U-turn. In the Haringey Local Plan released in February 2015, policymakers describe their ‘Vision for the Area’ as: “The creation of a collection of thriving creative quarters, providing jobs for the local economy, cultural output that can be enjoyed by local residents, and places for local artists to live and work.”

So begins the momentous task of legislating an alternative way of living – coming up with what might sound like a contradiction in terms, a “warehouse blueprint”. Normalising an alternative lifestyle whilst retaining its authenticity is a tricky balancing act. W.H.A.T. member Tom Peters says: “Blueprinting is about trying to ring-fence off areas in a way that limits the rampage of gentrification across the city. The state is supposed to be hedging against these big development models. Otherwise the city will become unaffordable dead space.”

This might be what beckons for Hackney Wick, just a few miles down the River Lea, where the artist community has never tried to officially change its use from light industrial to residential or live/work.

As developers put in gigantic planning applications, artists are working out their notice period in leaky studios with nothing but vague Section 106 promises of “affordable workspace”. Going for legitimacy might mean the council makes you put banisters on the staircases, but it also offers protection.

When I get Askler on the phone, known as simply Shulem to his tenants, he tells me he “deserves a reward” for how he has developed the warehouses. “It’s a vibrant and fantastic community. We’re trying so hard to keep it like this. Of course! We could have gone for planning permission and built a Berkeley Homes out of it, but it’s crazy, these people do so much for the community. We have over 1000 tenants, not one single one of them takes housing benefit.”

While the council’s decision to draft a warehouse policy is generally thought of as “pretty progressive, for Haringey”, many of the residents – especially those familiar with the implementation of City Hall’s London Plan – express concerns about the council’s strategic policies to bring back the employment function of the area. This means big change. Local historian and founder of online forum Harringay Online Hugh Flouch says the boom and bust story of the British Industrial Revolution can be read in the history of this sprawling site.

Heavy industry arrived around 1914 in the shape of the redbrick Maynard’s sweet factory, Courtney Pope Holdings and a collection of piano manufacturers. Industry has been trickling out of Harringay since World War II, and many question exactly which types the council thinks it could tempt back. John Gregory, son of Jim Gregory who opened J. Reid Pianos in 1952, has worked in the piano refurbishment shop on St Anne’s Road since he was 12 years old. He says:“The factories have gone and have been converted. What was industrial is now residential.”

Except it is not just residential. The site is already home to the kind of burgeoning creative industry that the council says it wishes to create. The judge in the enforcement case at Ex-Fed recognised Provewell’s point that under the current occupation the building was generating a higher level of employment than when it had been used for its lawful purpose.

Gardens at the back of Omega Works. Photograph: Ossi Piispanen

Popularity problem

With Haringey Council tentatively on board, the other threat is the district’s ‘popularity problem’ or gentrification. The clumsy waves of big money are already appearing, one frozen yoghurt shop at a time. A shop called Simply Organique is the latest addition to Manor House Station – its healthy wares incongruous against the dusty fug of kebab grills, knackered bakeries and greasy spoons. Nathan Coen, 24, moved to Overbury Road from Dublin in 2010 and now lives in Omega Works. “When I moved it was just before the Tottenham riots, no one wanted to be here. Now you can see the changes creeping.”

But while it is easy to point the finger at the wider market for the rent rises, the internal organs of the warehouse district are not immune from profit-motives. Within the tangled power structure some ‘bad apple’ leaseholders are taking a less than positive artistic licence and making big bucks by squeezing bedrooms into former communal space. Gardiner, who is a leaseholder himself, says: “It’s a problem, and it’s not sustainable.” W.H.A.T. hopes to tackle the problem by starting a housing cooperative together with Provewell and taking on units themselves.

Using Haringey Arts as a vehicle to connect with its tenants, Provewell has invested £50,000 in the area’s external appearance. A huge hand-made light-up sign shaped like a cotton reel reading ‘Artists’ Village’ hangs over Overbury Road. There is also a heat-reactive mural depicting both the dystopian and utopian elements of warehouse life which turns opaque when you place your hands on it, and a QR code bookshelf encouraging passers-by to download a warehouse-recommended read.

Tom Peters from W.H.A.T. sees the ‘Artists’ Village sign’ and the landlord’s artistic patronage as a commodification of the area’s hitherto organic creativity. “It is branding. There’s a tension between wanting to celebrate what we are doing and preserving it.” But Co-Director of Haringey Arts James West disagrees: “Artists complain about having no funding, and that they can’t get Arts Council funding because of the cuts, but there’s money on the doorstep. So yes it is loosely gentrified, but at least you are being involved.”

When compared to the whopping towers of Woodberry Down or the gradual erosion of artistic areas like Hackney Wick, it is tempting to see the growth of the Harringay warehouse district as a genuinely bottom-up or grassroots process of regeneration. Peters resists such a simple narrative. “It’s not as linear,” he says. “The city is created and recreated all the time and it is a more complex process than looking at it top-down or bottom up. It’s about different interests clashing.”

See more of Ossi Piispanen’s photography here