Finding Bedlam: A skeleton's eye view of the Crossrail Project

No one talks much about the bathos of the Crossrail project, the mismatch between the grandeur of its design and the drabness of its ultimate function.

For all that the widely publicised story of its construction has gone heavy on the sublime – high-viz figures dwarfed by machinery in the underground caverns they have dug and now gaze at in wonder – and for all that it is the largest project of its kind in Europe and will cost £14.8 billion, there is no getting away from the fact that its true purpose, the reason for its existence, is that if you live in (say) Reading, you will be able to get to Central London that little bit quicker. The intended product of all the staggering toil and ingenuity is to facilitate more efficient commuting.

Which is not to take a disparaging view of the project but just to observe that the line between the marvellous and the everyday is thin. Crossrail is still in the future, so we are still far enough away to be able to see what lies on the marvellous side of that line. As we get closer to it and begin to use it, only the hum-drum aspect will remain in view: it will take an imaginative leap to see the system’s magnificence and complexity once we come to speak of it only as a form of transport that may be late, crowded or broken.

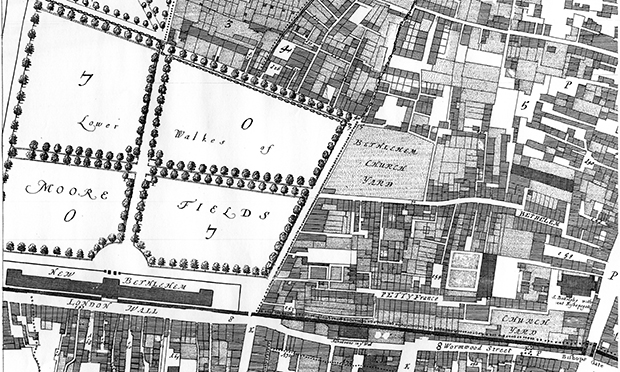

It’s the other way round with a human skeleton face-down in the mud outside Liverpool Street station. Since last year, many such finds have been uncovered during the excavations for Crossrail to the east of the City. Photos of encounters with human remains – including plague victims and inmates of St Mary of Bethlem (Bedlam) asylum – joined the high-viz hero shots in Crossrail’s publicity archive.

Everything that is sensational or horrific about such an experience is up-front and centre: the imaginative leap required in this case is to see the bones being used the way we usually use bones – to hold our bodies up as we conduct our daily lives.

It’s a leap that Crossrail lead archaeologist Jay Carver has no trouble making. “I must say that if I hold someone’s jaw or skull in my hand I can’t help but feel connected,” he says. “This is an individual who lived all those hundreds of years ago.”

Time is important. “With prehistoric remains you are so far detached from those individuals and the lifestyle they led,” says Carver. “Whereas dealing with the human remains from the Bedlam burial ground is so much more immediate and recent – we can imagine these everyday Londoners like ourselves who are buried there. There’s a lot more of a response to those modern remains.”

Some of the post-medieval remains are being studied for further insight into the biology of the virus that caused various London plagues, but all will be re-buried in the Willows Cemetery on Canvey Island, continuing Londoners’ tradition of extramural burial. The dig is now down to the Roman layer, the time at which London first became a major population centre.

It’s a rare opportunity, according to Carver: “We know quite a lot about Roman London from excavations undertaken over the last 50-60 years,” he explains. “But at the moment down at Liverpool Street it’s a part of Roman London that’s not been previously under investigation, so whatever I find is going to be new there.”

Empathy with the bones’ original owners has in some cases been made more difficult by the people who put them there, such as the “gruesome” find of an old cooking pot full of bones. “We don’t really understand necessarily, you know, the attitudes in the Roman times towards death and burial,” Carver says. “It became quite standardised over the centuries but there are also quite a lot of strange things going on – decapitation, the reburial of skulls in different areas; you don’t quite understand the mindset but I think these discoveries are really interesting.”

There is always something to learn from the deposits, in other words. But Carver points out the bones’ intrinsic value is, like that of art, down to their one-of-a-kind nature. He warns: “Archaeological heritage is an irreplaceable asset, you can’t get it back one it’s gone.”

The everyday life of humans has not always been lived in the same way. Finding and imagining different ways of living is fascinating. Far in the future, if other societies replace and forget ours and dig up the old tunnels, Crossrail will gain a new fascination as being part of the daily life of people long dead. It will be marvellous again, and people will talk about its pathos.

“Civilisations rise and fall,” says Carver, “and in some cases in the past have just disappeared into the jungle. We don’t know if that’s going to happen to us.”