Tech giant Cisco moves in to Hackney Community College

The international IT firm Cisco has announced it is moving in with a group of Hackney University Technical College (Hackney UTC) students.

Hackney UTC’s building in Shoreditch has some extra space, with just 25 students making up the final intake before the flagship technical college closes its doors later this year.

One of a number of efforts by its parent organisation Hackney Community College to give local young people an early start on the career ladder in East London’s swelling technology industry, the UTC didn’t work out.

But Hackney Community College’s relationship with Cisco is thriving, culminating in an expanded partnership with the tech giant. Cisco’s global incubator for technology research, CREATE, comes to Hackney as part of the Internet of Things (IoT) scheme promised £45 million in government funding.

Hackney Community College is also primarily government-funded, but its coffers are shrinking year-on-year due to budget cuts, making the extra cash a welcome boost.

“We could use the money,” Principal Ian Ashman admits, adding that the new centre will act as an “on-site employer.”

As part of the deal, Cisco has promised mentors for the college’s students, teaching sessions on new innovations that they are providing, and Cisco-accredited courses.

This partnership is one incarnation of efforts to address Hackney’s ethnic minority employment gap, by ramping up business partnerships that funnel talent into East London’s dominant tech industry.

Ashman’s approach is pragmatic, takes a decidedly business-first angle: “This is about human resources, not corporate social responsibility” he says. “If we want it to be sustainable it’s got to bring real business benefits.”

But compared to demand, jobs are in short supply.

Routes into Hackney’s growth industries are few and far between for Hackney’s most deprived career-seekers. Ashman says plainly: “We don’t have as many employers signed up as I would like to have.”

Qualifications on the rise

On the qualifications side, Hackney’s students have done well overall.

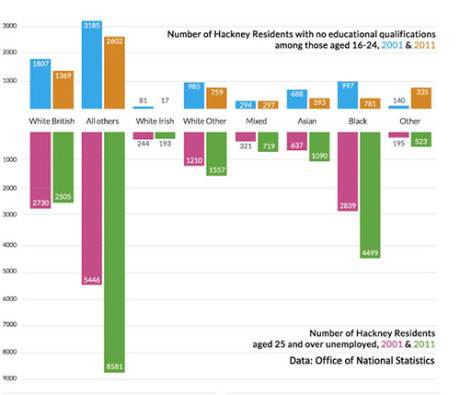

Educational qualifications are on the rise across the board, arming all ethnic groups with further hope of gainful employment. Among all ethnicities, between 2001 and 2011, the number of 16-24 year olds in Hackney with no qualifications dropped 4.1%, from 16.9% to 12.8%.

Duncan Melville, chief economist at the Centre for Economic and Social Inclusion, says that we may be still be awaiting the full effect of a more qualified population: “There’s been a massive improvement in education outcomes for all ethnic groups in London as a whole, in the last ten years. We may not yet be seeing the full impact of that.”

But employment inequality between White British populations and ethnic minorities continues to rise, according to new research by the Runnymede Trust comparing census figures from 2001 and 2011.

The makeup of Hackney’s unemployed over the ten years shows a patchy picture for Hackney, with some ethnic minorities faring far better than others in reducing unemployment.

Hackney’s Black residents, the borough’s largest minority group, reported increasing unemployment rates over the ten years. But the borough’s second and third largest ethnic minority groups, the White Other and Asian populations, both saw improvements in unemployment rates over the same period.

Inequality on the rise: Figures show employment inequality between White British and ethnic minority residents increased between 2001 and 2011. Visualisation: Paul Coomey

Blacks hardest-hit

The Runnymede Trust’s figures show that Hackney’s Black residents, making up about 25% of the population, were hardest-hit by unemployment, despite improvements in qualification levels.

In 2001, 15.9% of Hackney’s black population aged 16-24 held no qualifications; by 2011 that rate had fallen to 9.6%.

But over the same period, unemployment rose for Black residents aged 25+, from 15.7% in 2001 to 19.4% in 2011.

Hackney’s White Other and Asian populations both suffered less unemployment over the ten year period, by 6.5% and 1.6% respectively; the proportion in these groups with no qualifications each went down by about 9%.

Unemployment for the White British population dropped from 6.9% in 2001 to 5.2% in 2011. The number of White British with no qualifications dropped 5.8%.

Stagnant improvements

The study shows that in the noughties Hackney made relatively little headway on reducing ethnic inequality in employment overall.

Over the ten years, there was no change in Hackney’s absolute inequality measure for employment, reporting a 7.4% difference between the white British population and the overall minority population.

Fewer and fewer 16-24 year olds have no qualifications, but Hackney is now the worst borough in the country for unemployment among ethnic minorities.

In 2001 it was the fifth worst, with relative improvements in other boroughs like nearby Haringey and Tower Hamlets bringing Hackney down in the rankings.

Supply and Demand

At Hackney Community College, Ashman has managed to secure several apprenticeship schemes with locally-based digital firms such as online DIY stationer Moo.com, and the creative agencies Poke and Mother.

His pilot Tech City Apprenticeship scheme for ethnic minorities offered up 20 work/study placements paying around £18,000 a year. He received 50 applications per place from all over the country, but only accepted students from East London.

Another scheme with Goldman Sachs placed eight out of 10 participants in full time work upon completion.

But lobbying the tech industry’s recruitment channels has limited his schemes’ scope. Most businesses take on mainly graduate level, unpaid interns and rely heavily on word-of-mouth recruitment.

“Anyone from a poorer working class background — which by virtue of statistics means you’re more likely to be black – is going to find that route harder,” says Ashman.

“Tech city tends to recruit people who are already in employment,” says Ashman. “When I first started a conversation with the tech companies three years ago, they operated a system of unpaid internships into employment.”

And size does matter. When companies get beyond a certain size, worldwide corporate recruitment policies can scupper locally-based negotiations, putting giants like Google, and tiny operations lacking infrastructure for apprentices, out of reach.

“I’d love to work with Google!” Ashman affirms. But for the moment, mid-size operations of about 200 employees are the sweet spot for mining apprenticeships.

Hackney Community College’s apprenticeship schemes are still in their infancy, making outcomes difficult to measure.

“We don’t have any reliable data, but I suspect they’re having an impact” says Ashman. “But we need more employers to sign up and join.”

For the moment, businesses have the upper-hand here, as educators tailor course offerings to the technology industry’s specific needs.

On the hierarchy of useful skills for educators, being a savvy business relationship-builder is up there with intellectual prowess. And for students not at all interested in technology? Here’s hoping for the Shoreditch Arts and Humanities Roundabout.