Major exhibition about abstract art opens this week at Whitechapel Gallery

Theo Van Doesburg, Colour Design for ceiling and three walls 1926-1927. Courtesy Galerie Gmurzynska AG. Copyright the artist. All rights reserved

You can argue all you want about abstract art – what it means, when it came about or whether it’s good or not – but there’s no denying it was the single most potent movement in modern art. Now, a new exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery is looking to put some of these arguments to rest. Adventures of the Black Square: Abstract Art and Society 1915–2015 uses Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square as its starting point. It aims to show how art relates to society and politics, and includes the work of over 100 modern and contemporary artists, including Piet Mondrian, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, David Batchelor and Aleksandr Rodchenko.

What’s the significance of holding the exhibition now, in 2015?

The reason we wanted to do it in 2015 is that we really feel that the starting point for abstraction is 1915, with Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square painting. It was shown in St Petersburg in 1915 at an exhibition called The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings: 0.10, which symbolised a utopian vision that artists wanted to achieve. For artists at the beginning of the 20th century this empty void of a black square represented a break with the hierarchical conventions of academic subject matter and the beginning of a really progressive art and egalitarian society. So it was really ambitious and it was imbued with a lot of hope. We look at it now and see a black square but at the time it was such an important gesture and really quite a radical one for the period.

What’s the rest of the exhibition like?

We’ve got 103 artists and more than 250 works. The title is Adventures of the Black Square, which sort of belies the colour and excitement that visitors will experience. It’s quite an explosion of colour and shape and form, from photographs to sculpture to painting. It should be quite a sensory and overwhelming experience.

‘Abstract’ is a fairly loosely applied term. Are there strict rules to what makes a work of art abstract?

No, and I think that is the key to the exhibition. The rules may have been strict in 1915, but the ways and the different paths artists have taken abstraction in are really interesting. What joins them all together is that they have abstracted notions of the world and have made them visual. You can look at a painting, an installation or sculpture and understand that at first glance it may not be apparent what the work is about. But the more you look, the more it gives you a completely different optic, allowing you to view the world in a completely different way.

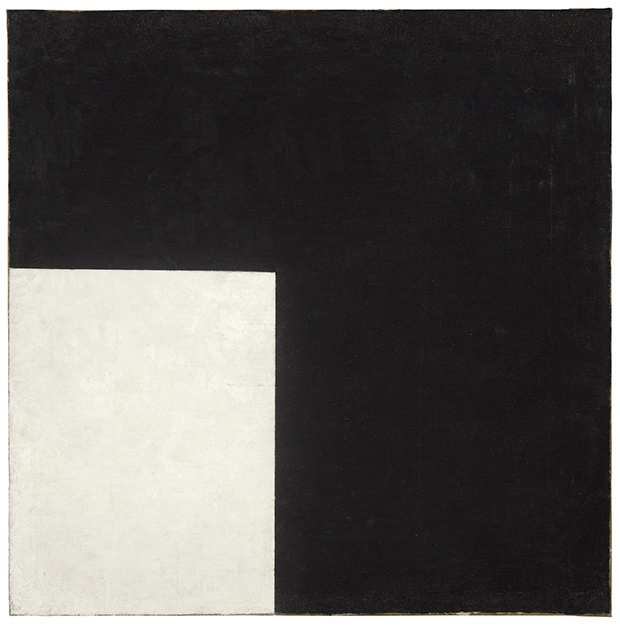

Kazimir Malevich – Black and White Suprematist Composition 1915. Image courtesy of Moderna Museet Stockholm

Did the sheer volume and variety of abstract art make the exhibition difficult to put together?

Not really. I think if we’d just chosen to do an exhibition on abstract art there could have been hundreds and hundreds of works that could have been included. But we wanted to focus on artists that had used the language of abstract art to articulate ideas about politics and society. And so that’s the key that anchors the exhibition and runs throughout the show.

How does the exhibition view the links between art, society and politics?

I think as you go through the exhibition there are examples at every turn of artists who have used abstraction to articulate ideas about the world. There’s a work by Keith Coventry, who is a British artist, from a series of paintings called the Estate Series in the 1990s, based on the large plans of London housing estates. He chose to paint an aerial view of these housing estates, and the paintings as you see them could have been done in 1915 by Malevich in that he uses that same language and abstracts the notion of a housing estate. You really feel that it should belong at the beginning of the exhibition because of the form that it takes but it’s actually making quite an important statement about the world we live in.

Why do you think many people find abstract art difficult to relate to?

I think that to the vast majority abstract art is quite confusing and difficult but we’re offering a way in really, a way of understanding how, by using a very clear visual language, artists can make a real valid comment on both the world that surrounds us and its politics. We’ve also tried to make it as global as possible, so there are artists from virtually every part of the world, to show how it wasn’t just in a cornerstone of Russia that people were producing these extraordinary works.

What part of the exhibition are you particularly drawn to?

We’ve been working on it for quite a while now so I feel full immersion, but we’ve been lucky enough to work with David Batchelor, a British artist who has made a new presentation for the Whitechapel in which he uses a camera to take pictures of what he calls ‘found monochromes’, which are white squares he sees all around the city. Whether it’s a blank billboard, a note stuck on a shop window or blank screen, he will take a photo to show how abstraction is all around us and an integral part of the city we live in. We’ve done a big installation in one of the galleries which is an explosion of white squares and rectangles, which acts as a nice counterpoint to the black square.

Adventures of the Black Square: Abstract Art and Society 1915 – 2015 is at Whitechapel Gallery, 77-82 Whitechapel High Street, E1 7QX from 15 January – 6 April