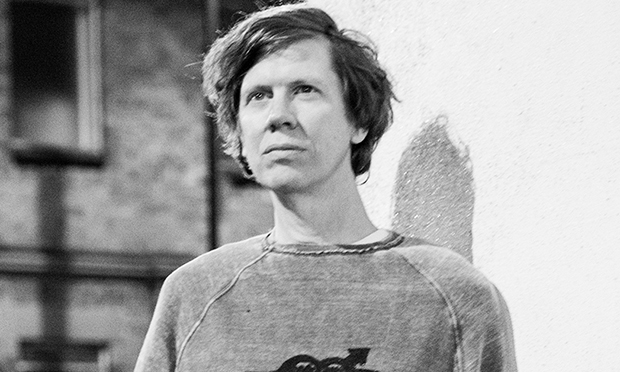

Thurston Moore: 'London reveals itself really personally to everybody who lives here'

The summer of 1981 was long and cruel: average temperatures in New York City pushed 30°C and the air was a sticky wet. The United States had entered recession and unemployment had almost doubled since the previous winter. The new president, Ronald Reagan, wouldn’t be proclaiming “morning in America” for another three years – this was what seemed like the endless night before that morning (which, for many, still didn’t amount to much when it arrived).

Just half a decade earlier, New York City had been so close to bankruptcy that police cars had been mobilised to serve papers on the banks. It’s hard to believe that the Bowery, now lined with luxury apartments, was once a litter-strewn pocket of petty – and not so petty – crime. (The state’s annual murder rate was well over 1,500.) In some ways, it was closer to the New York of Travis Bickle or even Snake Plissken than that of Lena Dunham and Girls.

But one night that summer, outside the Stillwende club in the Tribeca neighbourhood of lower Manhattan, a pair of guitar players in their early twenties whooped into the air in what a friend later remembered as an exhibition of “spontaneous exuberance”. Thurston Moore and Lee Ranaldo had just run out of the venue after playing one of their first shows as Sonic Youth, a performance in which Moore had, at some point, swapped his guitar for a snare drum (which he bashed) and Ranaldo had wielded a power drill attached to a microphone.

When Hüsker Dü released their album New Day Rising in 1985, the title’s grand announcement only underscored what music fans had known for years – in rock, at least, something exciting, something other, something else had arrived.

Sonic Youth was at the centre of that exciting-other-else. Consisting of Moore, Ranaldo, Steve Shelley and Moore’s ex-wife Kim Gordon, the band fused the experimentation of New York’s No Wave and post-punk scenes with sugar-coated pop and rock, while adopting the unfussy, cerebral attitude of the city’s burgeoning art community. Albums such as Daydream Nation (1988) laid out the template that Pavement, Sebadoh and countless other bands would develop in their own ways, in increasingly divergent directions.

And their influence was such that it extended beyond their music – when Moore and Gordon announced their decision to separate in 2011, Salon ran a vaguely embarrassing article (by a stranger to them both) that began with the sentence: “I didn’t react well to the news that Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore, king and queen of the indie rock scene, were getting divorced after 27 years of marriage.” Despite never having crossed over to the mainstream in the way that, say, Nirvana or the Smashing Pumpkins did, they’d gone from being music icons to being icons, period.

When I meet Moore at Homa on Stoke Newington Church Street, he is curiously bashful and self-effacing, as if still settling into success after decades as an established artist. He is 56 years old but seems ageless: boyish, polite and engaged in his craft with a teen’s thirst for discovery. He’s also the first to puncture his own reputation as an icon of any kind. After our introductions (we chat about movies), he tells me he was initially “a little afraid” of working with his new bassist, Debbie Googe, best known as a member of My Bloody Valentine and Primal Scream.

“I’d known Deb through the years, from when Sonic Youth and My Bloody Valentine would play together. We never really talked very much – it was mostly ‘hi, bye’,” Moore says. “I’d just seen one of [My Bloody Valentine’s] first reunion gigs in Brixton and I remember distinctly being impressed by Deb’s stage presence. She was really moving the engine of the band. I was just, like, ‘That’s really good.’ I didn’t think in my mind, ‘I want that.’”

When James Sedwards, his new guitar player and a friend of Googe’s, suggested a collaboration, Moore felt: “Maybe it’s too strong for me right now, because we’re just trying to get something together. Maybe my thing is not enough work – or on a level she’s used to, playing larger venues. I thought, ‘Are you willing to play small venues in the middle of England in front of 50 people?’” Such anxieties evaporated when Googe and Moore finally met to talk things over. “She was completely charming. And when we started playing gigs, I knew right away that it was such a great choice.”

Thurston Moore’s new band (from left): Debbie Googe, Steve Shelly, Thurston Moore and James Sedwards. Photograph: Phil Sharp

I tell Moore I’m surprised that he feels nervous – almost star-struck – in the company of musicians whom most would consider his peers. Does he feel intimidated by them? “Yes, certainly,” he says, without hesitation, and veers off into an anecdote about a talk John Lydon recently gave at Rough Trade East near Brick Lane as part of a book tour. “I just met Johnny Rotten for one second,” he enthuses, awed by his brush with British punk’s original agent provocateur. “He has an extremely low threshold for bullshit. He’s also a humanist – he’s very interested in humanity and people’s personal worlds being sacred to them. He’s kind of a demonised celebrity for the most part – but he’s gracious to people and still retains a lot of the pain that brought him to that personality . . . he had a fucked up childhood.”

Moore says his own upbringing was “benign”. The son of a university lecturer, he was raised as a Catholic in the suburbs of Bethel, Connecticut, and gravitated to New York for no reason other than to explore its music. “When I moved there, I was all of 18, 19 years old and New York was primarily a demographic that was older than I was – you know, the Ramones and Patti Smith were all in their mid- to late twenties. So I felt very young. I knew there were other young people moving to the city who were responding to what they were hearing coming from the CBGBs/Max’s kind of world and most of those people were hard-bitten, runaway artists and poets, like Lydia Lunch.”

Coming from a life of relative comfort, Moore initially felt out of place. “My interest in what was going on was really much more personal. I was a loner. I wasn’t part of that instant community of the denizens of No Wave, living in squalor,” he says. “I kept to myself so I was able to study what was going on around me. But I was fascinated by the lineage of New York, from the Warhol Sixties to the Poetry Project at St Mark’s Church – certainly William Burroughs coming back to the city after living in London for so long. All these people were in the neighbourhood and I could see them physically.”

It seems a world away from Stoke Newington, where he has been living since last year – an increasingly upper-middle-class neighbourhood whose name has become a byword for young parents shopping for quinoa at Whole Foods. But he says that London reminds him of his life in the early 80s, as it’s “still a little rough”. New York has been “glazed over with money, but it doesn’t have the sheen of money here.”

I ask why he chose Stokey. “Oh, because Eva lived here – the woman I’m in love with.” He says this with a disarming certainty. Moore then tells me how this personal decision soon brought about professional serendipities. “She was living on Stoke Newington High Street in a flat she was renting that musicians have used through the years as a famous little hovel. That’s how I met James [Sedwards]. She was, like, ‘There’s this incredible guitar player who lives downstairs and he’s incredibly sweet and polite and plays guitar like I’ve never heard before.’ I met him in the common kitchen. He made me some tea and we sat down and started talking about records, records, records, records. And he was a Sonic Youth enthusiast. In fact, I’d met him in 1991 – he’d snuck backstage at Reading when we played there with Nirvana and Iggy and the Ramones. He was a 15-year-old lad and his friends and him said hello to me. I had a vague recollection of this happening, actually. So all these years later, I met this person and started playing music with him.”

But Stoke Newington had other associations, too – he used to stay here in the 80s at the crash pad of Richard Boon, the former manager of the Buzzcocks and a Rough Trade employee who now works at the local library. Since that time, the area has undergone “incredible change” – he speaks wistfully of how improv nights were once held at the old Vortex club, which occupied the site now taken by Nando’s. I say that London writes over itself quickly and he agrees, but adds: “It also reveals itself really personally to everybody who lives here.” When we finish up our drinks and start walking towards our homes, I see Moore wave at an acquaintance, get excited by a table of Matchbox cars at the Hackney Flea Market and chat with a furniture seller about a shelf. He seems very much at home.

The Best Day by Thurston Moore is out now on Matador Records

Yo Zushi’s new album It Never Entered My Mind will be released by Eidola Records on 19 January