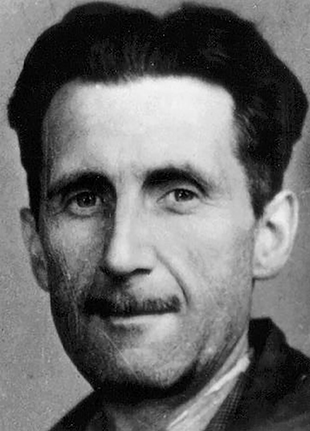

George Orwell's East London footsteps

In the not so distant past, London’s East End was a place to be forgotten, an area readily associated with disease, overcrowding, alcoholism and crime. Either you had the misfortune of living in one of the area’s slums, or you simply stayed clear.

Or, if you’re George Orwell, you quit your steady well-paid job and hit the streets.

In 1927, after five years serving the British Empire as a police officer in colonial Burma, Orwell traded his uniform for rags and spent a few months living a life of abject poverty in two of Europe’s grandest capital cities. He recounts his experience in Down and Out in Paris and London, published in 1933.

In many ways, this experience defined Orwell’s writing career. The poverty he witnessed in London’s own backyard came as an eye opener after years of service in the Imperial Indian Police. Here was Great Britain preaching enlightenment to all corners of the globe, yet in Spitalfields and Whitechapel the living conditions were as bad as in the slums of Calcutta.

The seeds had been sown. Over the following two decades Orwell would use his words to fight social injustice and imperialist and authoritarian rule. His righteous causes would be developed novel after novel, and ultimately culminated in the publication – sixty five years ago next month – of 1984.

So what has changed since the time of Orwell’s writing? What has become of the East End lodging-houses that played such an instrumental role in his writing career?

The simple truth is that most of the squalor he experienced no longer exists here. Many of the buildings, however, do still stand – though under a very different guise.

The Providence Row Night Refuge “for deserving Men, Women, and Children” on modern day Crispin Street used to provide accommodation for more than 400 destitute people, and did so from 1860 until as recently as 1999. Inmates would get a bed for the night, as well as a ration of cocoa and bread. Nowadays it’s a student residence for the London School of Economics. Students may not have much money but it’s fair to say these are two very different levels of poverty.

The Brune Street Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor opened in 1902 and as it its name suggests used to provide nourishment for the Jewish community of Spitalfields. In the 1960s it was still regularly feeding 1,500 clients. The establishment has now been divided into expensive flats.

Fieldgate Street’s Rowton House, also erected in 1902, offered 816 beds. It is known for a fact that George Orwell stayed there, as did Soviet revolutionaries Maxim Litvinov and Joseph Stalin when they attended the London conference of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1907. American author Jack London called it the “Monster Doss House” packed with “life that is degrading and unwholesome”. Today it is known as Tower House and offers a vast array of luxury apartments, some worth more than £1 million – a far cry from the shilling Orwell had to pay for a night’s rest.

These are but three examples of the many East End establishments that have gone from rags to riches in less than a hundred years. Back in Orwell’s day these institutions existed to assist the poor, now the buildings they were housed in serve a wealthier class of person.

But times have changed and so has the area. Would Orwell roll over in his grave at the thought? Perhaps not. In many ways we have people like George Orwell to thank for this progress.

Jack the Ripper’s infamous murders in 1888 made international news and the area saw unprecedented regeneration thereafter. Orwell’s work brought East End misery back to the forefront of social agendas and ensured the regeneration triggered by the Ripper years didn’t stop there.

Whereas people used to avoid the area and even fear it, nowadays people of all walks of life flock to the area to tour the sites – a celebration of immigration, poverty and murder if you will. Thanks for your help George.