Tree of life: African Community School helps kids dig up family roots

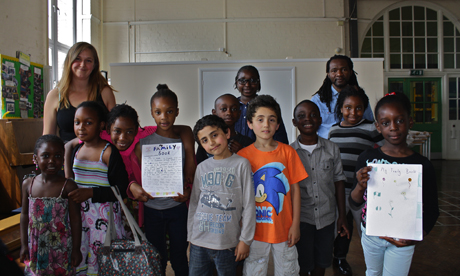

Children at the African Community School. Photograph: Kalyeena Makortoff

Adjusting to life in the UK was a challenge for Felmina Finn. The Jamaican-born 72 year-old still remembers fighting for a factory job as a young black immigrant after years tending farm animals in her home country.

It is a story never before shared with her eight year-old granddaughter Julietta, who is enrolled on a family history course being run at Dalston’s African Community School (ACS), a supplementary educational programme for ethnic minority students.

In one of Princess May Primary School’s computer labs, 11 students are delving into their family tree and talking to their fathers, grandmothers and siblings about life in their home countries.

Instructed by journalist Martha McAlpine and primary school teacher Joseph Essombe, the course gives children of immigrant families a chance to connect with their heritage – an opportunity these seven to nine year-olds might otherwise miss.

“Hackney is a multicultural place, and these children are bound to be leaders in the future,” says Essombe. “But what kind of leaders, if they don’t know their own history? If you don’t know where you come from, you’re bound to be lost.”

Teaching children about the histories of their own families is just one way in which the ACS has filled an unintended shortfall in the national curriculum when it comes to providing support to first and second generation immigrants.

Over the past 13 years, the charity has offered three to 16 year-olds revision and booster classes for subjects like maths, science, languages and history, personal health, social education, and a range of extracurricular activities like African drumming, world art and design technology.

School director and founder Frank Owuasu says the Saturday courses and summer school were developed in an effort to tackle underachievement in children of African and Caribbean descent, but were open to all ethnic and faith groups in the area.

With 20 staff and a ten-student cap on class sizes, the programme gives students total contact and develops focus in their studies, says Owuasu.

“The results are just unbelievable,” he adds. “We’ve produced doctors, professional people, and they go back into their own communities and do well and inspire others.”

Many students have come back to work as ACS support staff after they have graduated, Owuasu notes, and the programme is now a regional model, inspiring Turkish and other African community schools in London.

But engaging students with their roots has to be the first step, says Essombe.

“We tried to put to them that they shouldn’t be shy about where they come from,” he adds. “It’s valuable. Everyone has their own part of history.”

As a journalist, McAlpine helped formulate the questions for an oral history styled interview between the students and family members. But the task was harder than expected.

Many immigrant families have trouble sharing their stories, even with their children.

Essombe was 17 years old when he moved to England from Cameroon, and he only recently learned about his own roots and family tree, which stretches back to the royal family in his home country.

He says a feeling of insecurity among those within the immigration system means many people who have recently moved to the UK from African countries want to stay out of the spotlight and are even mildly suspicious of questions about their backgrounds.

But exposure to questions about roots and lineage at an early age is bound to open up discussions later in life, he adds.

Eight year-old Grace Clegg knew little about her Nigerian family before the course started. Over 10 weeks, she’s heard about aunts and uncles, and even a grandfather she didn’t know was alive.

She is planning to learn more about her relatives ahead of a visit to Nigeria this year.

“You’re planting the seed now, for them to be aware that this is very important,” says Essombe. “That will engineer their value, wherever they are in their future.”