Art of noise: overheard by the overground

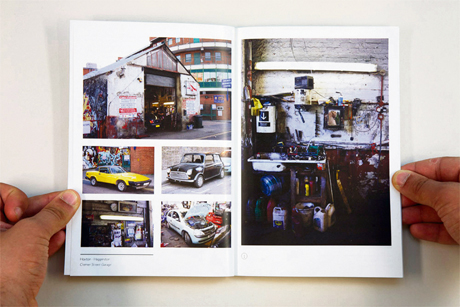

Garage sounds: Cremer Street mechanics in their workshop

It’s not uncommon to get on a train and see your fellow passengers absorbed in their headphones, closing themselves off from the city they are travelling through.

But for multi-disciplinary designer Ross Aitken, the rise of private listening was the inspiration for the Oversound project, a soundtrack for rail journeys on the Overground’s East London line which aims to connect passengers with the world around the stations they visit.

“I have been living in Dalston for the past two years and have a lot of friends in South London so I was very familiar with the Overground and the East London Line in particular,” says Aitken.

“I think travelling by Overground train or bus is always a more intriguing experience than the tube, because you are offered a view of the city around you. However, unless you make the effort to actually get off the train and explore these places then they remain something familiar yet unknown and intangible.

“After two years of travelling that same route, I wanted to know what really went on in all those places I had seen from the train window and I wanted to provide other commuters the chance to experience them too, albeit in a fairly abstract sense.”

Aitken walked the length of the line several times during the initial stages of the project, making recordings of goings-on in the areas around the train line.

“It was my intention to discover aspects of each neighbourhood I walked through that would speak for themselves in a sense. I made the walk from Dalston to New Cross a number of times over the weeks I was recording just looking for interesting places that I felt would betray something of the atmosphere and character of an area.

“I was really trying to record things that were not only geographically unique to an area, but that would produce interesting sounds that would not necessarily exist elsewhere; the sound of a cars’ echo in Rotherhite tunnel, or the bicycles on the canal tow path in

Dalston.

“Other samples came from my personal interaction with people in the area, such as some mechanics at Cremer Street Garage near Hoxton station. I felt the garage said something about East London that is not so easy to find anymore.

“They were happy to help and wonderful to record; there were some priceless examples of cockney banter that are seldom heard just walking down the street, especially in more gentrified areas like Dalston.”

Londoners reacted in different ways to Aitken as he recorded them. “In some situations it was necessary to not only alert people to my presence but ask their permission to make a recording. I quickly learned it was easier to make my recordings as subtly as possible to capture an authentic atmosphere and avoid confrontation.

“One person on Ridley Road Market was particularly obstructive and took real offense to my recording, even though I wasn’t remotely concerned with what he was doing.

“Most people however, either pretended not to notice me or else were intrigued and even helpful. It prompted a lot of

interesting conversations. ”

Once he’d amassed a library of audio, Aitken contacted several musician friends, as well as sound artists, some linked to the SoundFjord sound art gallery in Tottenham, to translate the recordings into ten tracks, one for each of the journeys between the eleven stations on the East London Line from Dalston Junction to Surrey Quays.

Aitken provided the musicians with a brief to make the project cohesive. “Having made the samples for each journey, I separated the sound files into different folders for each part of that journey.

“For example, in the sample folder for Dalston to Haggerston, there was one subfolder containing samples from Ridley Road Market, another with samples from Gillette Square, another from Kingsland Road and so on.

“I requested that the musicians use at least one sample from each of these to create a detailed audio-portrait of the area, though how prominently each sample featured in their final composition was entirely up to them.

“I also instructed the artists not to place samples in a geographically chronological order since this would mean the tracks only matched the journey in one direction. I wanted the tracks to be interchangeable, so the soundtrack would work regardless of whether the listener was travelling from north to south or vice versa.

“I instructed the musicians not to think of their track as the journey from Dalston to Haggerston specifically (for example), but rather a reflection of the space between those two stations.”

What Aitken has assembled is a broad collage of East London in 2012; cockney voices, and those of middle-class children, mix with the sounds of bicycles, cars, and, of course, trains, and the whole is tied together by a pulsing undercurrent of electronic music.

In a sense it accurately describes the overlap of cultures; there are tabla drums as the train passes through Whitechapel, piano melodies as the train emerges into Surrey Quays, and, throughout, snatches of everyday conversation in a range of languages.

For sounds, and interactive map and more go to oversound.co.uk, or ross-tb-aitken.com.