The Master and Margarita – review

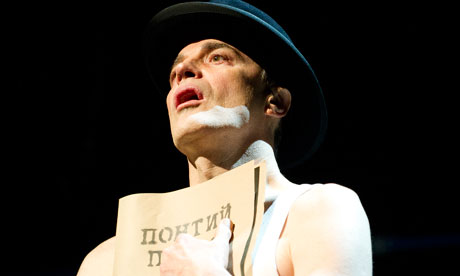

Paul Rhys in Complicite's The Master and Margarita at the Barbican. Photograph: Tristram Kenton

Andrew Lloyd Webber’s ill-fated attempt at adapting Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita for the theatre led him to pronounce the great Russian novel unstageable. In film, no lesser icons than Roman Polanski and Federico Fellini have tried and failed to transfer the tale from page to screen. So who would dare to venture where such greats have stumbled?

Step forward Simon McBurney. As a founder and artistic director of Complicite, McBurney has quietly become a doyen of modern British theatre, consistently challenging convention by utilising all manner of dramatic devices in the company’s increasingly inventive productions. This project presented him with the biggest trial to date, and it comes as no surprise that the resulting work is so compelling.

In many ways, The Master and Margarita provides a perfect platform for McBurney and Complicite. The fantastical novel merges myth, fact, reality and fantasy to the point of incomprehensibility, and no company is better equipped to transport that turmoil to the stage. Within the opening few minutes we are treated not only to a plethora of themes, but also to a visual extravaganza which is nothing short of spectacular. As such, deconstructing the plot is an almost impossible task. Suffice it to say that there are so few longeurs in this piece that the colossal 180 minute running time seems positively abrupt.

The success of the production lies in its unwavering commitment. True to form, Complicite throw everything including the kitchen sink into this adaptation. Video projection, puppetry, fruit, audience involvement, visual effects and comic book style graphics are all added to the mix; the ghosts of previous failures to bring this to the stage forever banished. The boldness of the scenes and the vigour and confidence of the acting accounts for most of the play’s power and we are transported by a string of expertly orchestrated set pieces from one surreal world to another. Moscow is very much a character in the play, and the scenes involving Margarita flying over the city are breathtakingly effective.

In concentrating so closely on getting the intricacies of the narrative perfect, McBurney has sacrificed some of the humour of the original novel, but there are plenty moments of comic relief, mostly involving Behemoth, the wild-eyed, foul-mouthed cat in Satan’s entourage. Attempts to modernise the play with references to iPads and Primark, and to localise it with comments such as “it’s a bit like Russell Square” in reference to a location in Moscow, never seem to dilute the narrative, but rather add some contemporary resonances which may otherwise have been overlooked.

John Hodge’s Collaborators, a blackly comic take on Mikhail Bulgakov’s last years, has just had its run extended at the National Theatre, and the two plays make interesting companion pieces. But while the one seeks to navigate inside the famed author’s mind, the other takes his most famous output and expands it in ways previously unimaginable. McBurney’s triumph is in seeing this most complex of novels as a foundation on which to build, rather than as a restrictive structure. The joy of the production lies in its ability to transcend its source material, and the result is the most fun you’ll have with a Russian dramatist all year.

The Master and Margarita is at the Barbican Theatre until 7 April.