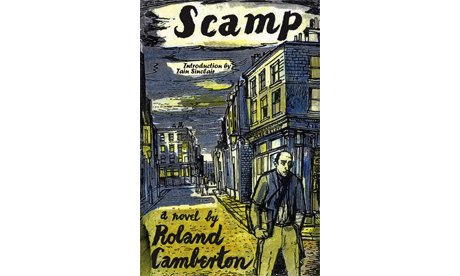

Scamp, and Rain on the Pavements – reviews

Scamp by Roland Camberton: review by Josh Loeb

This is literature as it once was – before computers, before postmodern silliness, in the immediate aftermath of the War, when there was still everything to play for.

Scamp has recently been brought back into print – with a terrific introduction by Iain Sinclair, who seems to get his oar in everywhere these days.

The Haggerston psychogeographer tells of his hunt for Camberton – real name Henry Cohen – a Hackney Jewish lad and a pupil at Hackney Downs School in the 1930s.

The novel’s protagonist is Ivan Ginsberg, a writer in the days when you really could eke out enough to pay the rent on cheap lodgings in Bloomsbury by dashing off pulp fiction for two bit publications or undertaking run-of-the-mill hack work in Fleet Street.

In his quest to realise his dream of editing his own magazine (Scamp, a daring literary journal for ‘the younger generation’) our hero introduces us to oddballs including exhausted journo Bert Flogcrobber, an oleaginous ‘demi-millionaire’ of indeterminate Eastern origin, suburban divorcee Mrs Chabbers and the hangers-on of scruffy West End bohemiana.

It is in the gusto with which Camberton fleshes out his characters – and his evocative descriptions of the melancholic skies above Bloomsbury and Fitzrovia and the streets of Soho – that this book’s charm lies.

Poor Flogcrobber is “the man-in-the-street, the middle-aged, worried, tax-paying, rate-paying father of a family, a professional man who had risen in the world, but whose speech had not lost an ugly flavouring of diluted Cockney. The snarling phobias, grievances, and vanities hidden beneath this drab exterior were no more visible than with any other season-ticket holder coming out of Cannon Street station at ten o’clock in the morning.”

St Paul’s at sunrise is “a luminous grey”, and beyond it that “great, flat bulk of the city, over which the spidery fingers of the dawn crept”.

This is good, honest prose. Prose you could bite into. In its themes and youthful flaws, Scamp is not unlike Orwell’s Keep The Aspidistra Flying. Inexperienced excitement streams from its pages like ink from the pen of a writer getting carried away with his newfound talent. Here are the scribblings of a young beat poet scurrying from garret to tram stop to nicotine-stained café, observing and making notes along the way.

It wouldn’t have a hope in hell of getting published nowadays. That it was 60 years ago was only because John Lehmann – a champion of Orwell who had the necessary resources – happened to have a fetish for male, metropolitan, proletarian writing of this kind.

And maybe it was also because the worlds of publishing and journalism were less elitist, less detached, than they are today – a sad reflection on our times.

As for Camberton, he was a strange and tragic figure – a private man and “the Great Invisible of English fiction” according to Sinclair. Scamp won the Somerset Maugham Award.

Thank goodness he had the chance to publish something as raw, addictive and of the streets as Scamp.

Whoever the Camberton of our times may be, let’s hope a publisher somewhere takes a punt on him.

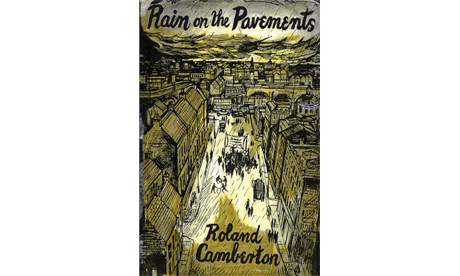

Rain on the Pavements by Roland Camberton: review by Jonathan Knott

Many changes have occurred in the borough since Camberton wrote, but the Hackney that he portrays is still recognisable. It’s an area that can confound, inspire, and grind down in equal measure – but to which, in any case, many of its residents form a deep, unique attachment.

The book follows the path of David Hirsch from his early boyhood to his emergence as a young poet with a scholarship to study in France. Through David’s eyes, and through a succession of portraits of his formative influences, we witness his development alongside the political and social upheavals of the 1930s.

David’s explorations of London begin as a six year old, accompanying uncle Yunkel, three years his senior, on trips across the city “to Hampstead, to Purley, to New Cross, to Wanstead Flats”, in awe of his apparent ability to steer and drive the trams.

But he soon finds his world restrictive. ‘Allergic’ to the Talmud, and to exercises with titles like ‘two men seize a prayer shawl’ or ‘an ox gores a cow’, he falls in with a gang of young recalcitrants at the synagogue who drop stink bombs and prompt the exasperated Rabbi to rail against the ‘epicureanism’ of their generation.

It is, however, the epicurean characters in the book who seem to have the most benign effect on David: such as idle Mr Essand, only energised when teaching his pupils chess moves, and uncle Jake, who gave up a respectable career as a tailor to write and teach himself philosophy, leading a bicycle-powered, hand-to-mouth existence to the scorn of his family. His heroic toil eventually results in the publication of a novel, tragically titled Failure.

Jake joins the RAF and becomes reluctant even to mention the book. “He wanted to return to London as rarely as possible, and never to the districts and people he had known”. But David was to conclude that “the pleasures of the intellect are deepest and most abiding” and Jake was therefore “a lifelong voluptuary”.

We witness the backdrop to the close-knit, supportive but inward-looking Jewish community in the casual anti-Semitism of David’s schoolmates and his Daily Mail-reading games master, in the blackshirts loitering on the street corners, and, chillingly, when the story flashes forward to a reunion with a childhood friend in France. The friend bitterly complains about ‘work and poverty’, as it emerges he was the only one of his family to escape deportation. (Nor does Yunkel return from studying the Talmud in Poland.)

In this context it is easy to sympathise with David’s preference for the contradictions of life as it is lived over the destructive certainties of those around him: the Rabbis, the Etonian communist who laments the fate of the poor living in “the slums of Hackney”, the socialist meetings his friend Stanley attends, or a fascist demonstration “lit by the dim, grey blue lighting of Stoke Newington Road”.

Hackney is ever present, its geography providing the day-to-day texture of David’s experience. As he grows older, he is increasingly beguiled by and drawn towards the bohemian ‘urban fairyland’ of Soho. But it is still, in the end, a love of, obsession with, or at least, inability to ever really escape from, his home borough that proves decisive in his development.

—

Scamp and Rain on the Pavements by Roland Camberton are now back in print. Published by Five Leaves and available in local bookshops.