The thin grey line

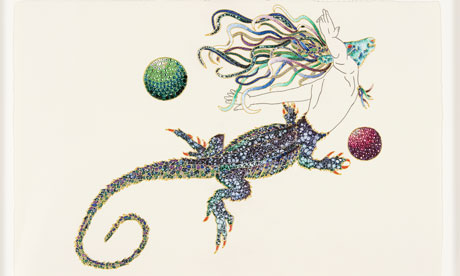

Seymour Suite, 2010, by Raqib Shaw

Summer is the time for commercial galleries either to shove a bit of stock on the walls and go on holiday, leaving some minion or other to mind the shop, or to do something more adventurous. White Cube in Hoxton Square, London, has mounted a large and ambitious drawing show, Kupferstichkabinett: Between Thought and Action, a survey of more than 200 drawings by 55 artists hung in groups and clusters and runs, at least two deep, around sombre, dark walls. The atmosphere is studious and quiet, the viewers attentive as they nose up to the frames or peer down into a number of vitrines.

Here are etchings of heads and bodies by Lucian Freud; a gridded-up preparatory drawing of a dining recess by Patrick Caulfield; a sketch for a neon sculpture of a man masturbating by Bruce Nauman. Freud skates a needle across a prepared copper plate as he draws heads on pillows and the bulk of Big Sue the Benefits Supervisor. Caulfield takes a sharpened pencil and dutifully traces and copies 1960s furniture, a Sunday supplement style for living that now looks quaint and retro. Tracey Emin remembers and draws blindly through a sheet of carbon paper, peeling it back to reveal the bluish smudges and the line, a lamp-post and a girl on her back on the Margate esplanade. Is the drawing for us or for herself, the artist just wanting to see what a memory looks like?

Some drawings, such as Caulfield’s, are made out of practical necessity, a step on the way to making a painting. Others satisfy different but no less urgent needs – the needs of the ego and the libido, the unstoppable urge to invent; sometimes it is to keep up a constant supply of market product. A drawing by Damien Hirst may be scurrilously bad, with its doomy scribbled pronouncements about mortality, but it is cheaper to buy than a skull or a shark in a tank.

Drawing is the basis of all art and visual thinking, writes Deanna Petherbridge in her magisterial new book, The Primacy of Drawing. Drawing renders thought visible, she says. But what thoughts are these, running around the walls? Say Something Once Why Say It Again, writes Harland Miller in capital letters, quoting a Talking Heads lyric. Then he repeats it, on another sheet of paper. Why say it at all, you might ask. More interestingly, you might ask about the difference between the written word and the drawn word. Gabriel Orozco’s Fast Mind drawings look so cursory as to be mere traces of the hand’s passage, drawn so fast that thoughts can’t keep up. The drawing itself is the thought, not some idea that preceded it.

Orozco’s thin wandering lines, arcing and snaking, may just be an elegant way of occupying the blank proposition of a sheet of white paper. But it is hard not to see bodies emerging out of this emptiness. Orozco’s line has both vitality and reserve. He knows when to stop.

An artist’s hand might draw with an innate elegance and authority, or it can be clunky, like a shout, or tentative and full of doubt. Julie Mehretu’s drawings always appear as a kind of rushing, hurrying energy, layer after layer of scratches, dabs, dabbles and judders as she switches from graphite to watercolour, ballpoint pen to bits of coloured tape. Some parts of her drawings are slow and deliberated, others are a tangle of colliding marks. Does it all add up, or is it just so much excitation and energy?

However physically insubstantial a drawing is, it is a complex, even profound activity. Petherbridge writes of what she calls “graphic incontinence”, the inspirational excess and uncontrollable urge “that leads an artist to draw constantly on any available surface”. Many of us who are not even artists engage in this sort of thing, in constant doodling and scribbling and jotting without purpose. Drawing can be a kind of fiddling, an orchestration of what might otherwise be a kind of itch and scratch. Drawing belongs as much to the body as the mind, the hum and fizz of the nervous system.

Drawings reveal: they are often more accessible and intimate than the sculptures and paintings in whose wake they often come, or which they anticipate. And because most of us have the experience of drawing, even though we may profess to be no good at it, drawings have a kind of familiarity and directness we can feel at home with. They demand close attention; they stay with us in ways other kinds of art don’t. Petherbridge notes (paraphrasing Walter Pater) that while most painting at the beginning of the 20th century aspired to the condition of drawing, a hundred years on most drawing aspires to the condition of the sketch. A lot of artists now, you might think, aren’t in a position to aspire to more.

But as the White Cube’s show demonstrates, drawing goes much further than sketching. Raqib Shaw’s sea monsters and richly detailed sexualised gods seem to aspire to the condition of jewellery, while Jake and Dinos Chapman have made cramped, peculiar, bucolic scenes of a fantasy Germany, signed and dated as though they had been drawn by Adolf Hitler, wannabe artist, at the close of the first world war. They are like fake historical documents. Michael Landy’s careful pencil portraits take a kind of sixth-form acuity to a level of compelling strangeness. Gary Hume’s deceptively schematic works are drawn both on paper and on the glass or Perspex frame, creating real shadows and the illusion of modelling as one walks around them.

Drawings can be tender or belligerent, introspective or stupid, even frightening and intense. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s jumbly, coarse heads, Rachel Kneebone’s confusions between the body’s insides and outsides (women’s torsos and limbs writhing into colons and penises) and Fred Tomaselli’s constellations of stars, galaxies and drugs: all are conceptually as well as physically rich.

A drawing might be labour intensive or take a few seconds. Which is better? Nobody knows. Otherwise banal artists can show a real talent here; beefed-up reputations can show their weaknesses. At best, drawings are closer to a lover’s secrets or a midnight conversation than a speech at a big public occasion. The drawing as grand machine or mere demonstration of skill and effort doesn’t interest me: it declares its labour before anything else.

Petherbridge’s 500-page study should convince anyone of drawing’s centrality, its often apparent simplicity and also its deep mysteriousness. Hers is a great book, written by someone who both draws and thinks seriously about an activity in which it is often almost impossible to tell what was made 500 years or five minutes ago. The form transcends its time, and the mores of the moment, while being always grounded in a period or an epoch, a specific moment of engagement. If drawing is a language it can also be a parting remark, something said on a street corner as a friend turns and walks away that wounds you and you remember always.

The Primacy of Drawing by Deanna Petherbridge is published by Yale University Press.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News & Media Limited 2010

Published via the Guardian News Feed plugin for WordPress.