Seeing through Kingsmead Eyes

When someone is photographed, they become special, important, worth looking at; but they also become objects, to be looked at. How can those represented also tell their own stories?

Acclaimed photojournalist Gideon Mendel has struggled with this question throughout his twenty-five-year-plus career. “It’s something I’ve never quite resolved,” he says.

For his latest project, jointly conceived with Kingsmead Primary School in Homerton, Mendel tackled this problem by inviting his subjects to become documentary photographers themselves.

As well as taking portraits of all the school’s pupils, eventually combined in a large composite image, he and fellow photographer Crispin Hughes gave them cameras and trained them to document their own lives.

The result is Kingsmead Eyes, a collaborative exhibition in the Bethnal Green Museum of Childhood, co-funded by the school and Sanctuary Housing Association.

For Mendel, resident in Hackney for 17 years, it involved “finding photographic meaning as much around the corner as on the other side of the world”.

His composite portrait is striking and compelling. The kids meet your gaze full on, solemn, unsmiling. You look into serious eyes; and if you turn around, you can look out from those eyes too.

On the opposite wall are works by the 28 children who participated in the project: each has contributed one photograph and an accompanying handwritten poem.

The poems were written with the guidance of Joelle Taylor, poet-in-residence at the school for the past two years, where she is known as “the rapping lady”.

Her beatbox poetry workshops, says headteacher Louise Nichols, “have been a huge success in helping the children to express themselves”, especially important when 85% of pupils do not have English as a first language.

The school’s decision to collaborate with these leading artists and to entrust the kids with Panasonic Lumix cameras (most of which survived), demonstrates its commitment to creative excellence. As Mendel says, he wanted to “go somewhere special, different.”

And they did. Some media coverage has presented the exhibition as a novelty: a sort of highbrow “Kids Say The Funniest Things”.

But these works are worthy of attention not because they’re created by ten-year-olds from a deprived part of London, but in their own right.

The photographs, selected by Mendel and Hughes together with the children from over 3000 images, are oddly beautiful, moving snapshots of lives as they are lived.

Food features heavily: toasted sandwiches, chips and salad, gloriously coloured Smarties. Zainab Ahmed’s close-up of homemade cake, thick with icing and hundreds-and-thousands, might seem a comforting image without her accompanying text: I was a tiny cute baby when people came to my house / Such delicious food, / Licking their fingers, / I would stick out my hand wanting some / I am still waiting.

This arresting, unexpected gloss reminds you that children see the world as anything but straightforward.

Other representations reflect their personal significance to their owners. When Sefora Lema wears her ‘sparkling, magical, wonderful’ crown, she writes, ‘I’m the queen’. Especially viewed in the Museum of Childhood, these photographs evoke the real power of these treasured objects.

Terrence Aidoo has photographed three teenage boys, football champions; seen from below, against a bright blue sky, they look monumental, proud, heroic.

Family members appear often, offering glimpses of part-shared, part-hidden lives. Omar Kanyi’s photograph of a group of men in his living room takes you back to hovering on the edges of half-understood adult conversations.

But children see and hear much more than adults may realise. We see Jordan Lema’s mother through the kitchen door on the phone to his father in Africa; he writes of her efforts to stay brave and her private prayers. Kingsmead eyes see you.

Mendel’s previous work, particularly his award-winning documentation of those living with HIV/AIDS, proves him to be a highly political and ethically-engaged photographer, and the exhibition inevitably touches on contemporary social issues, such as one boy’s work in memory of his brother’s friend, stabbed ‘by a flick knife’.

But there are no didactic messages here. Socioeconomically and culturally, the Kingsmead pupils come from very mixed backgrounds: 95% are from ethnic minorities.

But Mendel wanted to “avoid romanticising” deprivation without denying the existence of “difficult, painful things in society”.

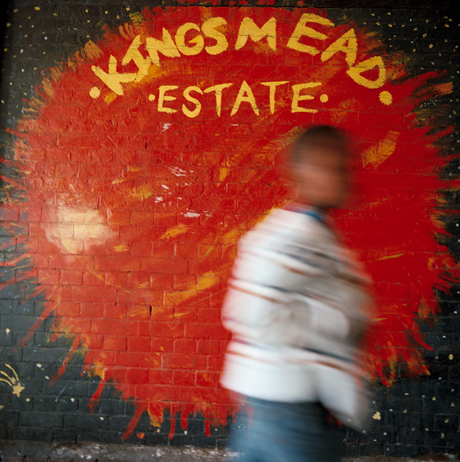

His own mesmerising images of the Kingsmead Estate came from his close involvement with the community, and provide the contextual overview which complements the children’s stranger, sideways takes.

The children’s photographs could be flatly read as indicators of class or culture, but what you see instead is their personal meaning: my balcony, my brother’s bedroom.

Dennis Fofanah’s photograph of an apparently unremarkable pair of closed curtains is transformed by his writing: ‘Behind the green curtain is a parallel universe’.

Echoing this, other children tell of ‘secret clubhouses’ and ‘secret games’. Temporarily, we are allowed into these private, magical spaces.

No adult, regardless of skill or experience, could have created these images and words. Secret games are only secret if you’re not playing too.

As Mendel says, “the holy grail of documentary photography is intimate access”, and nothing can “compete with the access a child has to their own life”.

By sharing their own lives, these children become not statistics or symbols but people, with richly individual existences.

Kingsmead eyes have seen, and this is what they saw.

The Scar

By Tafari Dyer

He was sixteen years old

Reckless and bad

Some said a man with a motorbike

And a head full of fast bends

He flew as a hill

And everything went black

He woke up in a hospital bed with a big scar

As long as a silver railway track

That led to his new dream

—

I laid down these words for you

By Kyle McDiarmuid

Out on my balcony

I saw a white shadow

It had eyes, a nose and a chin

I saw a glimpse of a light in a window

The curtain moves but no one’s there

But there was a face of fog

I went back in

It was following me

I put my hand there

It disappeared

It was a ghost

—

Kingsmead Eyes: A collaborative exhibition by Gideon Mendel and Kingsmead School 7 November 2009 – 7 February 2010 Front Room Gallery, V&A Museum of Childhood, Bethnal Green