Josh Loeb: Is nature healing?

Is nature healing? That’s a question some people have been prompted to ask amid reductions in human activity over recent months.

Sometimes they mean ‘healing’ in both senses. Are things like birdsong, trees and flowering plants soothing? Undoubtedly so.

But what about whether the natural world has been able to heal itself, having been given a bit of a breather from modern human activity in all its relentless restlessness?

Notwithstanding reports about a spike in hedgehog numbers, deer on suburban council estates and suchlike, according to scientists (and I work for a veterinary publication nowadays so I asked some), it’s too early to say whether or not wildlife has been ‘thriving’ these past few months.

Improvements to the state of nature often take time to become apparent, and the lockdown effect on animals has likely varied between species.

For example, there have been reports of various birds breeding more successfully this year because of fewer people out and about on nature reserves disturbing avian romances – though the loosening of lockdown and hot weather mean there are now probably more people than ever at some sites.

Ectoparasites are good examples of species that have surely fared badly since the introduction of social distancing.

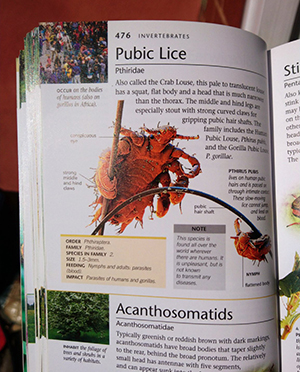

My children’s nits disappeared virtually overnight as soon as the schools closed – the R rate for nit infestations is definitely down – and the same presumably goes for the pubic louse (pthirus pubis).

I don’t have personal experience of it but that species is, one imagines, not enjoying lockdown at all – although perhaps it’s better to ask an expert like Professor Neil Ferguson.

Pubic lice are every bit as much wildlife as are birds and mammals – they’re in the Dorling Kindersley RSPB photographic guide to the wildlife of Great Britain, after all.

The dastardly coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, is, meanwhile, also part of nature, so perhaps we should be careful what we wish for. Nature’s great. Until it kills you or causes you to have itchy genitals.

Then there are humans. We’re part of nature too. Aren’t we?

At a local level we are blessed to have wildlife that people can marvel at in the palms of their hands (and I don’t mean nits).

In my younger years I made it my business to know which of my local rocks creepy crawlies were hiding under, and in recent weeks, with schools closed, I have needed no encouragement to share that childhood habit with my own children. It’s free entertainment. Good clean fun.

During the first week of lockdown we found a frog in our garden. Then we found a common toad and lesser stag beetle in West Hackney Rec – two very exciting discoveries in what is an almost postage stamp-sized, isolated wildlife refuge off the A10.

We’ve found smooth newts in Clissold Park and on Hackney Marshes. We even saw a grass snake swimming in the Waterworks Nature Reserve.

The pièce de résistance was a slow worm, a type of legless lizard, found at a location in a neighbouring borough just across the border from Hackney.

Photograph: Josh Loeb

Since the start of lockdown on 23 March I’ve counted dozens of species of bird and insect, five species of mammal, four species of reptile, three species of amphibian and a couple of different types of fish – all spotted and identified within a small, walkable radius of home.

If this amount of wildlife can be seen on brief walks with two tantrum-prone children (Memo to council: please re-open the schools), just imagine what could be found locally by ecologists with the time and resources to do proper surveying.

For some, though, no amount of wildlife will ever be enough.

I for one would love to see hordes of hedgehogs on newly carless Hackney streets, common lizards reintroduced to Stoke Newington Common or a colony of non-native wall lizards living on the rocks by the ornamental river in Butterfield Green (Please note: since wall lizards are an ‘alien’ species in the UK it would be a criminal offence to release any and I’m by no means advocating that anyone do so, but if a few were to just happen to turn up in my local park I wouldn’t be too unhappy about that either).

The George Monbiots of this world fantasise about repopulating the remote Scottish uplands with large carnivores – wolves, bears etc – but might cities be better places to kick-start that process, albeit on less of a wolf and more of a wolf spider scale?

Why does the concept of ‘rewilding’ so often seem to involve big stuff being reintroduced into far-flung parts of the UK that most people will never visit?

By contrast, a humble toad here or a lesser stag beetle there could enliven many an urban walk, just as it has done for me and my two children during the long months of lockdown.

Josh Loeb is senior news reporter for Vet Record and a Hackney resident. You can follow him on Twitter at @LowEbbs